The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie

HomeThe Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie

Sony Pictures | 2003 | 107 min | Rated PG-13 | Nov 14, 2023Movie rating

7.9 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 4.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Overview

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003)

Documentary about Robert McNamara, Secretary of Defense in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, who subsequently became president of the World Bank. The documentary combines an interview with Mr. McNamara discussing some of the tragedies and glories of the 20th Century, archival footage, documents, and an original score by Philip Glass.

Starring: Robert McNamara, John F. Kennedy, Fidel Castro (I), Errol Morris, Richard NixonDirector: Errol Morris

| Documentary | Uncertain |

| War | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 (48kHz, 24-bit)

Spanish: Dolby Digital 2.0

Subtitles

English, English SDH, Spanish

Discs

Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region free

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 4.5 | |

| Video | 4.5 | |

| Audio | 4.5 | |

| Extras | 2.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie Review

"I am very sorry that in the process of accomplishing things... I made errors."

Reviewed by Kenneth Brown December 7, 2023Stop reading. The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara is hands down one of the finest political/historical documentaries of all time. What director Errol Morris's long-form interview lacks in broad-scope insight -- it is, after all, wholly focused on one man's experience and perception -- it delivers in honest self-reflection and in-the-room-where-it-happened testimony. Whether McNamara has had a net-positive or net-negative effect on U.S. history (even he seems to struggle with the answer to that), his story, his "lessons", told in his own words, with shocking forthrightness, are fascinating and more relevant than each one has ever been. Add this to your watch list and collection post-haste. Back so soon? Good. I'll assume, then, that this one is already on the way from Amazon.

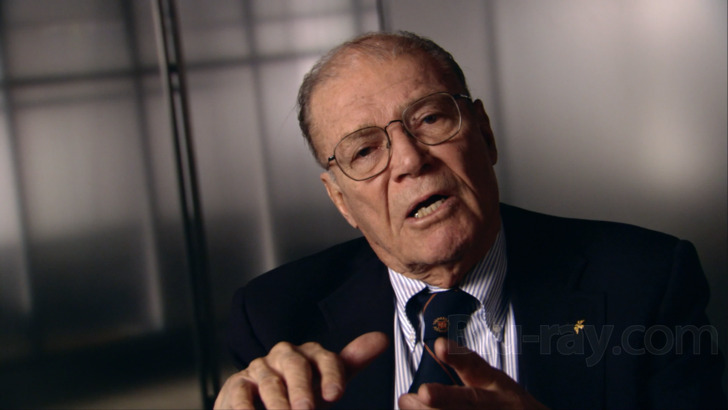

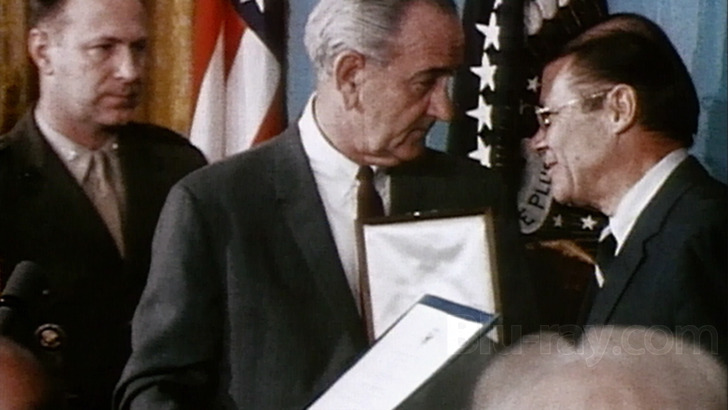

The legacy of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara is intrinsically tied to the events of the Vietnam War, and in many minds his decisions during this time define him as a war criminal. Having protested against the war, director Errol Morris detested McNamara. So, with questions to be answered, he decided to utilize a unique interviewing technique: the ingenious "Interroton Device", wherein the interviewee stares directly into the lens, creating the sensation of a first person conversation. McNamara expounds on the situations he encountered and the tough decisions he made. But rather than encountering a hardened war criminal, a belligerent know-it-all out to set the record straight, Morris found himself sitting with a reflective intellectual; a teary eyed old man. Cut alongside archival war footage and confidential audio recordings between Presidents Kennedy and Johnson speaking with McNamara at crucial turning points in history, the resulting work of art is a moving biopic of one manís life and a substantial block of world history. Bookmarked with eleven "lessons" Morris garnered from over twenty-three hours of interviews with McNamara, the Oscar-winning 2003 Best Documentary expounds upon the shortcomings of humanity and the havoc wreaked through unhinged war. McNamara declares, "I am very sorry that in the process of accomplishing things, I made errors," striking a dissonant chord of universal infallibility, leaving us all with much to contemplate.

Errol is one of the Documentary greats. He has an eye for subjects, a mind for the right questions and a fearlessness that's often unmatched. But for once, the filmmaker isn't the primary reason the end result is so good. McNamara is a vulnerable, willing participant; his shoulders heavy, his eyes dancing with tears, his lips trembling; not in weakness but in his knowing the exact measure of every stake and consequence of his life's work. He tells a deeply personal geopolitical story, elaborating frequently and elegantly, but rarely is any of his thoughts or comments designed to bolster his ego. He's counted his sins, or perhaps merely the sins he's accused of. Many times, over many nights, over many years. His eyes are haunted by past wars and long abandoned conflicts. His voice firm yet weary. The openness that accompanies his interview is astonishing and, as far as I know, unprecedented for a public figure of his stature.

But McNamara is also very aware that, at the time of the interviews, he's an ailing old man staring down barrel of the end of his life. He knows it, Morris certainly knows it. Takes advantage of it, as is his duty as the documentarian. McNamara succumbs to the draw of his mortality and blooms with information, some of which feels like things that he may not be supposed to share. (The news that The Fog of War existed had to make key government officials uneasy, and then, upon seeing the film, had to make the same officials quite angry with McNamara's frankness.) The former Secretary's thoughts don't dwell on legacy or trumpet his own accomplishments. His purpose is to document any bit of wisdom, knowledge or insight that might help future generations avoid the pitfalls he's learned are strewn across every battlefield; physical, mental and intellectual. He knowingly creates a time capsule with his Fog of War interviews, understanding that to do so properly requires his utmost candor, secrecy be damned. There are only a handful of topics he dodges -- really just a handful of specific questions he sidesteps -- but even then the truth echoes in his eyes. He knows his silence, or any nervous shift in posture or wince of discomfort for that matter, communicates a great deal. His silence is as articulate as his words.

And that's where Morris comes in. He gives McNamara room to be, well, a human being, full of faint contradiction, troubling emotion and presumably reliable but possibly unreliable memory. Even so, he keeps the "trial" of The Fog of War front and center, because this is, after all, a sort of prosecution of a man Morris has long believed to be one of the architects of the societal and geopolitical issues that plague the modern United States (circa 2003, although I'd argue the film is even more timely in 2023). McNamara may be a human being, but in Morris's eyes, he remains a peddler of war and death; a potential war criminal living free in the twilight of his life. He's clearly surprised by McNamara's openness, yet you can tell he never trusts the man. Morris is almost suspicious that it's all a ruse, cloaking dark secrets by covering them in shocking truths. McNamara is more than an observer of history. He stood in places where he could and did affect history; both for the U.S. and, to an extent, the world. What does that say? What questions does that demand of us, the real observers? How should we judge McNamara? Or the United States for that matter? Should we quietly sweep our lesser actions under the rug or take responsibility for the good and, perhaps more importantly, the bad? And how much can you or I, or Morris, really do to affect change when it only takes one man like McNamara to make decisions that have such sometimes awesome, sometimes terrible consequences? The Fog of War demands answers but only offers a few, all from McNamara, whose perspective, though incredibly interesting, can't ever be fully trusted. What a conundrum.

The Fog of War is divided into eleven chapters or lessons, which include:

- Lesson #1: Empathize with your enemy - "Kennedy was trying to keep us out of war. I was trying to help him keep up out of war. And General Curtis LeMay, whom I served under as a matter of fact in World War II, was saying "Let's go in, let's totally destroy Cuba. On that critical Saturday, October 27th, we had two Khrushchev messages in front of us. One had come in Friday night, and it had been dictated by a man who was either drunk or under tremendous stress. Basically, he said, "If you'll guarantee you won't invade Cuba, we'll take the missiles out. Then before we could respond, we had a second message that had been dictated by a bunch of hardliners. And it said, in effect, "If you attack, we're prepared to confront you with masses of military power. So, what to do? We had, I'll call it, the soft message and the hard message..."

- Lesson #2: Rationality alone will not save us - "I want to say, and this is very important: at the end we lucked out. It was luck that prevented nuclear war. We came that close to nuclear war at the end. Rational individuals: Kennedy was rational; Khrushchev was rational; Castro was rational. Rational individuals came that close to total destruction of their societies. And that danger exists today. The major lesson of the Cuban missile crisis is this: the indefinite combination of human fallibility and nuclear weapons will destroy nations. Is it right and proper that today there are 7500 strategic offensive nuclear warheads, of which 2500 are on 15-minute alert, to be launched by the decision of one human being? It wasn't until January, 1992, in a meeting chaired by Castro in Havana, Cuba, that I learned 162 nuclear warheads, including 90 tactical warheads, were on the island at the time of this critical moment of the crisis. I couldn't believe what I was hearing, and Castro got very angry with me because I said, "Mr. President, let's stop this meeting. This is totally new to me, I'm not sure I got the translation right..."

- Lesson #3: There's something beyond one's self - "WWII. The U.S. was just beginning to bomb. We were bombing by daylight. The loss rate was very, very high, so they commissioned a study. And what did we find? We found the abort rate was 20%. 20% of the planes that took off to bomb targets in Germany turned around before they got to their target. Well, that was a hell of a mess. We lost 20% of our capability right there. The form, I think it was form 1A or something like that, was a mission report. And if you aborted a mission you had to write down 'why.' So we get all these things and we analyze them, and we finally concluded it was baloney. They were aborting out of fear..."

- Lesson #4: Maximize efficiency - "We had so little training on this problem of maximizing efficiency, we actually found to get some of the B-29s back instead of offloading fuel, they had to take fuel on. To make a long story short, it wasn't worth a damn. And it was LeMay who really came to that conclusion and led the Chiefs to move the whole thing to the Marianas, which devastated Japan. LeMay was focused on only one thing: target destruction. Most Air Force Generals can tell you how many planes they had, how many tons of bombs they dropped, or whatever the hell it was. But, he was the only person that I knew in the senior command of the Air Force who focused solely on the loss of his crews per unit of target destruction. I was on the island of Guam in his command in March of 1945. In that single night, we burned to death 100,000 Japanese civilians in Tokyo: men, women, and children..."

- Lesson #5: Proportionality should be a guideline in war - "Killing 50 to 90% of the people in 67 Japanese cities and then bombing them with two nuclear bombs is not proportional, in the minds of some people, to the objectives we were trying to achieve. I don't fault Truman for dropping the nuclear bomb. The U.S. and Japanese War was one of the most brutal wars in all of human history. Kamikaze pilots, suicide, unbelievable. What one can criticize is that the human race prior to that time, and today, has not really grappled with, what are, I'll call it, "the rules of war." Was there a rule then that said you shouldn't bomb, shouldn't kill, shouldn't burn to death 100,000 civilians in one night?"

- Lesson #6: Get the data - "I was present with the President when together we received information of that coup. I've never seen him more upset. He totally blanched. President Kenndy and I had tremendous problems with Diem, but my God, he was the authority, he was the head of state. And he was overthrown by a military coup. And Kennedy knew and I knew, that to some degree, the U.S. government was responsible for that. I was in my office, in the Pentagon, when the telephone rang and it was Bobby. The President had been shot in Dallas. Perhaps 45 minutes later, Bobby called again and said the President was dead. Jackie would like me to come out to the hospital. We took the body to the White House at whatever it was, 4am..."

- Lesson #7: Belief and seeing are both often wrong - " I am more and more convinced that we ought to think of some action other than military action as the only program here. I think if we do that by itself, it's suicide. I think pushing out 300,000, 400,000 Americans out there without being able to guarantee what it will lead to is a terrible risk at a terrible cost. Let me go back one moment. In the Cuban Missile Crisis, at the end, I think we did put ourselves in the skin of the Soviets. In the case of Vietnam, we didn't know them well enough to empathize. And there was total misunderstanding as a result. They believed that we had simply replaced the French as a colonial power, and we were seeking to subject South and North Vietnam to our colonial interests, which was absolutely absurd. And we, we saw Vietnam as an element of the Cold War. Not what they saw it as: a civil war..."

- Lesson #8: Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning - "What makes us omniscient? Have we a record of omniscience? We are the strongest nation in the world today. I do not believe that we should ever apply that economic, political, and military power unilaterally. If we had followed that rule in Vietnam, we wouldn't have been there. None of our allies supported us. Not Japan, not Germany, not Britain or France. If we can't persuade nations with comparable values of the merit of our cause, we'd better reexamine our reasoning..."

- Lesson #9: In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil - "Norman Morrison was a Quaker. He was opposed to war, the violence of war, the killing. He came to the Pentagon, doused himself with gasoline. Burned himself to death below my office. He held a child in his arms, his daughter. Passersby shouted, 'Save the child!' He threw the child out of his arms, and the child lived and is alive today. His wife issued a very moving statement: "Human beings must stop killing other human beings." And that's a belief that I shared. I shared it then and I believe it even more strongly today. How much evil must we do in order to do good? We have certain ideals, certain responsibilities. Recognize that at times you will have to engage in evil, but minimize it..."

- Lesson #10: Never say never - "One of the lessons I learned early on: never say never. Never, never, never. Never say never. And secondly, never answer the question that is asked of you. Answer the question that you wish had been asked of you. And quite frankly, I follow that rule. It's a very good rule..."

- Lesson #11: You can't change human nature - "We all make mistakes. We know we make mistakes. I don't know any military commander, who is honest, who would say he has not made a mistake. There's a wonderful phrase: the fog of war. What 'the fog of war' means is war is so complex it's beyond the ability of the human mind to comprehend all the variables. Our judgment, our understanding, are not adequate. And we kill people unnecessarily. Wilson said, 'We won the war to end all wars.' I'm not so naive or simplistic to believe we can eliminate war. We're not going to change human nature anytime soon. It isn't that we aren't rational. We are rational. But reason has limits..."

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Sony's 1080p/AVC-encoded video transfer looks fantastic, particularly when McNamara appears on screen or when still images or the occasional film- sourced archive footage is utilized. Morris is a true filmmaker through and through, and The Fog of War is a visually striking documentary, cutting together news reels, wartime clips, maps, newspaper clippings, archive photographs, vintage recordings and more. Each element is subject to damage, specks, scratches, pixelation, macroblocking and other anomalies, but never because the documentary's encode is faltering. Every nick and blemish traces back to the original sources. High definition imagery is alive with warm colors, deep black levels and lifelike fleshtones. Contrast is a bit weak in a handful of shots but generally the detail on McNamara's face, shirt and tie are resolved crisply and naturally. Edges are clean and free of artificial sharpening, textures are refined and there isn't anything to the transfer that was unexpected or disappointing.

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Philip Glass and John Kusiak composed the music for The Fog of War and it lends strength, tension and even a sense of questionability to the documentary's surprisingly aggressive, push-n-pull pacing, all of which sounds better than it ever has thanks to the Blu-ray edition's excellent DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track. The soundscape is often front-heavy, as you'd expect from an interview-based doc. And McNamara's voice is as clear as you could hope. Vintage audio recordings have been cleaned and enhanced too, and the noise and wear-and-tear of the original audio elements, though very present and audible, aren't ever an issue. The rear speakers are active and involving, courtesy of the music and wartime sound effects. None of it sounds pasted on or unnecessary, and there's an art to the immersive experience that's been created for those paying attention to the subtleties of the sound design. Low-end output is strong and weighty as well, rounding out the lossless track and granting the film extra oomph and power.

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

Morris filmed more than twenty-three hours of interview footage with McNamara, so it comes as a bit of a surprise that Sony hasn't dug up a few more

to add to the documentary's Blu-ray release. Instead, we're given the same bonus content that graced the film's original DVD release.

- Additional Scenes (SD, 38 minutes) - Twenty-four deleted scenes are included, most of which have been wisely trimmed away to streamline the feature. Almost all of them, though, are worth watching, if only to garner more of McNamara's thoughts and stories.

- McNamara's Lessons from His Life in Politics - A text presentation of a document written by McNamara in which he details other lessons he's learned over his years as Secretary of Defense.

- Theatrical Trailer

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

The Fog of War earns its stripes and its Best Documentary Academy Award. Though a singular story of one man told from his perspective, Morris's interview with McNamara is full of insight, wisdom and frightening realizations of just how devastating the decisions of a small group of world leaders can be. The thought that one man, granted power and authority, could shift the course of the world so dramatically, is absolutely chilling, and you'll find yourself asking big questions long after the documentary credits roll. Thankfully, Sony has done the film a service with its Blu-ray debut. A terrific AV presentation is joined by all the doc's previously released supplements to deliver a must-own release. Highly recommended.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Fahrenheit 11/9

2018

Last Days in Vietnam

American Experience: Last Days in Vietnam

2014

Why We Fight

2005

The Gatekeepers

2012

Fahrenheit 9/11

2004

Untold History of the United States

Oliver Stone's

2012-2013

RBG

2018

An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power

2017

I Am Not Your Negro

2016

Where to Invade Next

2015

Best of Enemies

2015

Roger & Me

1989

Prohibition

2011

Waiting for "Superman"

2010

American Experience: Freedom Riders

2011

Capitalism: A Love Story

2009

The Atomic Cafe

1982

The Look of Silence

2014

Won't You Be My Neighbor?

2018

Let There Be Light

1946