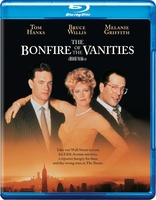

The Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie

HomeThe Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie

Warner Bros. | 1990 | 125 min | Rated R | Nov 06, 2012Movie rating

5.5 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 4.0 | |

| Reviewer | 2.5 | |

| Overall | 2.5 |

Overview

The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990)

The story of New York City bond salesman Sherman McCoy, who is charged with the hit-and-run of a young black man during an unexpected foray into the South Bronx while driving his mistress home from the airport.

Starring: Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith, Kim Cattrall, Saul RubinekDirector: Brian De Palma

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Comedy | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.77:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0

French: Dolby Digital 2.0

Spanish: Dolby Digital 2.0

Spanish: Dolby Digital Mono

German: Dolby Digital 2.0

Subtitles

English SDH, French, German SDH, Portuguese, Spanish

Discs

25GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region A, B (C untested)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 1.5 | |

| Video | 4.0 | |

| Audio | 3.5 | |

| Extras | 0.5 | |

| Overall | 2.5 |

The Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie Review

Burn, Baby, Burn

Reviewed by Michael Reuben November 28, 2012The Bonfire of the Vanities is remembered, if at all, as the highly regarded novel that some very successful and talented filmmakers turned into an expensive bomb. Much debated at the time was why such apparently surefire material as Tom Wolfe's bestseller produced such a dud of a movie. It certainly hasn't improved with age. Even before Bonfire was released, many predicted that the casting of Tom Hanks in the lead role of disgraced Wall Street hotshot Sherman McCoy would doom the picture. Others said Brian De Palma was the wrong director; literary adaptations were too far outside his comfort zone and, The Untouchables notwithstanding, DePalma's auteur temperament was ill-suited to the cross-winds of a major studio project. The year after the film flopped, critic Julie Salomon published The Devil's Candy, an inside account of the production, after which the conventional wisdom became that everyone dropped the ball, from the director and producers right on down to the lowliest crew member. But what if no one dropped the ball? What if De Palma made exactly the film the producers and the studio wanted, and Hanks was perfectly cast for it? What if the problem was, simply, that the producers and studio didn't understand what had made Tom Wolfe's novel popular and botched the translation to the screen? It certainly wouldn't be the first time. Obviously, a sprawling novel has to be compressed for film, and choices have to be made. But the script by actor and playwright (and, later, screenwriter/director) Michael Cristofer didn't just change the plot; it altered the central characters and transformed the entire narrative point of view. Producers Peter Guber and Jon Peters must have liked what Cristofer was doing, or they wouldn't have proceeded. (Then again, Guber and Peters may have been distracted by other projects, including their impending takeover of Sony Pictures, which they famously plundered from 1990 through 1994.) The Warner execs must have liked Cristofer's radical surgery as well, and if De Palma saw problems, he certainly didn't speak up loudly enough. But now that all the excuses and finger-pointing have faded into the past, it's clear that Bonfire was just another example of Hollywood's acquiring a pedigreed literary property with a distinctive voice that sold millions of books, then promptly jettisoning the very qualities that made the novel distinctive and successful. They kept character names, a setting and some basic plot elements, which they rejiggered into an ACME contraption that hurtled toward disaster as surely as Sherman McCoy's grey Mercedes when it entered the South Bronx. When all went wrong, no one could believe it was their fault and, like Sherman and his mistress, they started blaming each other.

Bonfire feels false from its opening frames. To understand why, one must go back to Wolfe's novel, his first after a successful career in non-fiction. Wolfe is a keen observer and a brilliant stylist. When he turned to fiction, he was no longer constrained by the obligations of a reporter and was free to express a lifetime of accumulated judgments on contemporary America—and Wolfe didn't like what he saw. Satire propels the narrative of Bonfire, sometimes cheerful, sometimes angry, but always intense and unrelenting. The voice that tells the story has a driving energy and a verbal dexterity unlike any other in popular fiction. Wolfe was equal-opportunity in his targets. He showered contempt on the Wall Street bankers with their sense of entitlement built entirely on debt, their wives wrapped up in a sense of superiority that they hadn't earned, the career politicians who praised "the people" so that they could better exploit them, the self-declared preachers preying on misery who did the same thing with Jesus, the prosecutors who didn't know right from wrong, the judges who cared nothing about justice, the journalists who wouldn't recognize truth if it bit them and every other rung on the rotting ladder of the social microcosm into which Wolfe transformed the New York City of the 1980s. Like the good journalist he'd been all his life, Wolfe knew every one of these people and the places they inhabited. Whoever and whatever he described had the unmistakable ring of authenticity. Wherever Wolfe took aim, he hit the target. By the end of Bonfire, he had drawn a portrait of an America that had merrily flung away every speck of decency, morality and notion of fair play. (And that was before the internet.) Readers loved the savagery, but the filmmakers didn't trust its mass appeal. So they tried to insert "likable" elements into a plot whose essential mechanics depend on every character behaving vilely. The results made as much sense as pouring chocolate syrup into a well-mixed martini. The central plot of Bonfire is the downfall of Sherman McCoy (Hanks), the bond trader and self-styled "Master of the Universe". That phrase is now common parlance, but it was Wolfe who popularized it as an ironic comment on Sherman's arrogance in believing that he and his ilk actually control the world. That illusion and the accompanying sense of entitlement are brutally stripped away after Sherman and his mistress, Maria Ruskin (Melanie Griffith), take a wrong turn into the South Bronx where an altercation leaves a black teenager injured and in a coma. The results are criminal proceedings and a media circus orchestrated by a politically ambitious D.A. (F. Murray Abraham), a publicity-hungry community activist (John Hancock) and a washed-up reporter desperate for a story (Bruce Willis). Overnight, Sherman is transformed from the toast of society into its latest meal. Where the novel of Bonfire charted Sherman's descent with pitiless precision (and Olympian indifference), the filmmakers wanted to engage our sympathy. So Hanks puts on an injured face, and De Palma rushes us through Sherman's scenes in the office so that he can linger over the rogues gallery of grotesques who victimize Sherman, starting with his wife, Judy (Kim Cattrall)—you know, that horrible woman who keeps Sherman's home and raises his daughter (a young Kirsten Dunst) while Sherman cheats on her with Maria. Cattrall makes Judy as shrill, nasty and mean as possible, and Cristofer's script eliminates the social context that Wolfe so carefully supplied to explain how a woman in her position ends up that way. What's left is a harpy pecking at poor Sherman who, it turns out, has been quietly suffering all these years, because all he wanted to do was please his father (Donald Moffat). There, there, poor man. With Sherman McCoy recast as the hero of Bonfire, and the ending suitably changed to let him "win", the mechanics of Wolfe's plot wobbled badly. Wolfe had provided a historically and socially accurate depiction of the New York criminal justice system, in which the defendants were mostly black and the judges and prosecutors were mostly white. The insertion of a white defendant into that system—and not just any white defendant, but one with a Mercedes, fancy suits and a Park Avenue address—made waves far beyond anything Sherman could have imagined, and Wolfe tracked their impact with an impersonal eye. Now, though, those waves were personified by prosecutors, cops, reporters, demonstrators, the sanctimonious Reverend Bacon (Hancock) and even the injured boy's mother (Mary Alice), who were all ruining the life of a supposedly likable fellow we were being encouraged to root for, as no reader of the novel rooted for Sherman. When you tinker with a carefully structured plot like Wolfe's, unexpected things happen. The black community of the South Bronx suddenly loomed as one of the biggest enemies in the film, whereas in the book everyone was equally culpable. Now the filmmakers felt obliged to fire Alan Arkin from the role of the presiding judge in Sherman's trial and replace him with Morgan Freeman. Although Arkin fit the character that Wolfe had written, Freeman provided an honorable African-American in contrast to the baying hounds led by Reverend Bacon. (Yes, I know that sounds crass, but the rationale was all but explicitly stated at the time.) Freeman also had the gravitas to give a climactic courtroom speech about "decency", even though the speech itself appeared to come from another world than that of Wolfe's novel. (It did.) Apparently, someone in the executive suite or the producing office decided that, besides likable characters, the film had to include an overt "lesson". The notion that a lesson could be provided without having a character stand center frame and speechify either didn't occur to anyone or didn't carry the day. The catalog of Bonfire's sins isn't quite done. One of the novel's most memorable characters is the bilious weasel of a tabloid reporter, Peter Fallow, who alternates between drunk and hung over and is on the verge of unemployment when Wolfe first introduces him. But luck hands Fallow the Sherman McCoy story, and his fortunes rise as Sherman's fall. Wolfe made Fallow British, but the character could easily have been American. (Steve Buscemi played a similar character three years later in Rising Sun.) At the studio's insistence, however, the part went to Bruce Willis, who was paid more than Hanks to help buoy the film's box office and not only failed to do so but also made a mockery of the part. Willis isn't entirely to blame, though, because Cristofer's script had already irretrievably sabotaged the Fallow character by making him the film's narrator and, in effect, its conscience. As Fallow suffers a mid-story change of heart, he becomes the voice mocking the orgy of misbehavior around him, even as he continues to gorge on its benefits. Wolfe's novel had a third-person narrator filled with righteous indignation, but the film was told by a smirking hypocrite. About midway through Bonfire, Sherman McCoy and Peter Fallow share a subway ride. The scene is ripe with irony, as we watch an adulterous Wall Street wheeler-deeler, for whom we're supposed to feel sorry, converse with an inebriated liar, whom we're supposed to respect. We're also watching two movie stars who look as lost as their characters. If you know Wolfe's book, you're wondering where the hell it disappeared to. If you don't, you're probably wondering what this movie was supposed to be about, and it's a damn good question.

The Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Reuniting with De Palma for the first time since Blow Out, cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond brought his distinctive sense of texture and color to diverse (exceptionally diverse) settings and landscapes where The Bonfire of the Vanities plays out its farces and tragedies. If nothing else, the film looked good. Warner's 1080p, AVC-encoded transfer has some minor problems but is overall an acceptable presentation, although it will no doubt be subject to the usual complaints about softness and lack of sharpness from eyes conditioned by digital acquisition and post-production. (Necessary disclaimer: I'm not saying that the products of such digital means are sharper, but they have inevitably set the subjective standard for what looks "sharp". Like people who have become accustomed to uncalibrated TVs and then have to adjust to a less contrast-y but more detailed image after calibration, viewers used to today's digital standards may not immediately recognize just how detailed the image on a Blu-ray like Bonfire really is.) Detail is good, colors are rich and varied without oversaturation, and blacks are deep without crushing. The lack of extras has allowed this 125-minute movie to reside on a BD-25 without major issues. The Blu-ray image's only noteworthy issue is recurring horizontal instability caused by gate weave, and although the issue is minor, it was sufficiently frequent to attract my attention.

The Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

According to IMDb, Bonfire received a 70mm release with a 6-track mix, but there is no sign of it here. Instead, we have the film's standard stereo surround track formatted in lossless DTS-HD MA 2.0. It's perfectly serviceable, in the sense that the dialogue is clear, there's enough ambiance with an appropriate decoding system to convey a sense of environment (e.g., in the opening tracking shot, when Peter Fallow moves from one location to another), and Dave Grusin's inappropriately jaunty score is adequately reproduced. What the track can't do is improve the movie, because the sound design is entirely consistent with the overall flawed conception.

The Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

Other than a trailer (SD; 1.33:1; 2:17), the disc has no extras.

The Bonfire of the Vanities Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

If anything, the decision to make Sherman McCoy's Wall Street banker the victim in The Bonfire of the Vanities looks even dumber today, when Sherman's successors are widely and justly despised for the havoc they wreaked on the economy some thirty years after Sherman himself was brought down by his personal failings. But it's not as if the makers of Bonfire had to foresee the future in order to realize what a mistake they were making. If they were too thick to grasp what Wolfe had written, all they had to do was watch Wall Street to see that big-time financiers make terrific villains—but "likable"? Only when the sun comes out tomorrow in Annie. Rent Bonfire if you want to see just how badly a great book can be mucked up by talented people. Then read the book.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

The Landlord

1970

Gentleman's Agreement

Fox Studio Classics

1947

Primary Colors 4K

1998

Delirious

Director's Cut | Special Edition

2006

Angels In America

2003

The Way We Were 4K

50th Anniversary

1973

Our Dancing Daughters

Warner Archive Collection

1928

Hi, Mom!

1970

Please Give

2010

Learning to Drive

2014

Salmon Fishing in the Yemen

2011

Nothing Sacred

1937

The Devil Wears Prada

10th Anniversary Edition

2006

Crimes of the Heart

1986

Lola Versus

2012

City Island

2009

Shampoo

1975

The Apartment 4K

1960

The Farmer's Daughter

1947

Syrup

2013