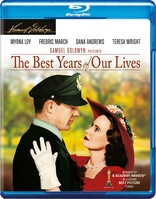

The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie

HomeThe Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie

Warner Bros. | 1946 | 170 min | Not rated | Nov 05, 2013

Movie rating

8.4 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 4.5 | |

| Reviewer | 4.5 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

Overview

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

Three returning servicemen fight to adjust to life after World War II.

Starring: Myrna Loy, Fredric March, Dana Andrews, Teresa Wright, Virginia MayoDirector: William Wyler

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Romance | Uncertain |

| War | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.37:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.37:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio Mono (48kHz, 24-bit)

Subtitles

English SDH, French, Spanish

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region free

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 5.0 | |

| Video | 4.5 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 1.5 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie Review

Starting Over

Reviewed by Michael Reuben October 28, 2013After winning the Best Director Oscar for Mrs. Miniver, Oscar's Best Picture of 1942, William Wyler took his own patriotic suggestion woven throughout that film and joined the Allied war effort. He served as an officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, applying his talents to military documentaries supporting the war. One of them, The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress, cost Wyler much of his hearing from flak concussions during aerial shooting over Germany. Wyler's first Hollywood feature after the war won him his second directing Oscar and was named Best Picture of 1946. The Best Years of Our Lives is the logical bookend to Mrs. Miniver, because it's about three American fighting men who have survived the battle, won the war and now have to face the years ahead. As he did often in his career, Wyler drew a practical template that later films about returning veterans would imitate. He had the advantage of working with a war that nearly everyone agreed was necessary and just ("nearly", because even in 1947 there were voices urging that the alliance with Stalin's Russia against the Nazis was a mistake, and one such character makes a memorable appearance in the film). But Wyler, who had grasped the dire urgency of the Nazi threat early on, was too much of a realist to ignore the human costs imposed by vanquishing such an enemy. He'd seen soldiers and pilots die in combat. He'd even lost a man under his command—and they were only making documentaries. On his return home, Wyler himself experienced the sense of dislocation and unfamiliarity so powerfully captured in Best Years. To give credit where credit is due, the script for Best Years was developed by producer Samuel Goldwyn, with whom Wyler's long and contentious working relationship ended with this film. Goldwyn commissioned war correspondent and novelist MacKinlay Kantor to write a screenplay, but Kantor ended up producing a novel in blank verse, which was published under the title Glory to Me. Robert E. Sherwood (The Petrified Forest) adapted Kantor's work for the screen. Wyler made additional revisions so that he could cast a non-professional actor named Harold Russell, whom he'd seen in an Army film called Diary of a Sergeant about the rehabilitation of injured war veterans. Russell would eventually make Oscar history as the only person ever to win two Academy Awards for the same role: one as Best Supporting Actor and an honorary Oscar for "bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans".

Best Years follows three veterans from Boone City, a fictional Midwestern town modeled on Cincinnati. They meet while trying to get home. Air Force Capt. Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), a former bombardier, finds all the commercial flights booked. In a classic Wyler staging, a businessman is behind Derry at the ticket counter with a porter carrying his golf clubs and luggage. He has a reservation. Since it's a movie, the juxtaposition isn't accidental, but what's the significance? Some directors might be tempted to linger on the golf clubs or make the businessman a pushy jerk, but not Wyler. He simply lets the scene play. You decide what it means that the war hero can't get a flight, while the businessman had a secretary to book him a seat. (Late in the film, a former soldier tells Capt. Derry that flyboys like him took all the glory, but grunts like him on the ground did the real work of winning the war. Everyone has a point of view.) Lugging his gear to the Army's Air Transport Command, where members of the military can hitch plane rides, Derry meets Sgt. Al Stephenson (Fredric March), who commanded soldiers in the Pacific theater, and sailor Homer Parrish (Russell), another Pacific veteran who lost both hands and hundreds of shipmates when his aircraft carrier sank in flames. Homer considers himself lucky, and he is proud of his dexterity with the prosthetic hooks the Navy doctors gave him. But he's concerned about how he'll be received by his family and friends. The three men bond on the flight home, and their approach over Boone City is exciting, as they spot familiar landmarks and exclaim over what's changed and what hasn't. But there's also a note of foreboding, as they fly into a new airport and sight hundreds of new war planes that will now be junked, because they are no longer needed. It's a visual reminder that the experiences that have consumed and transformed them for years are now as useless as scrap. "I've seen nothing", Stephenson will later say. "I should have stayed at home and found out what was really going on"—but no one understands what he means. One of the film's inspired narrative devices is Butch's Place, the bar run by Homer's Uncle Butch (Hoagy Carmichael). Homer points it out to them on their shared cab ride home, and it provides a locale for their paths to cross again in the future. Indeed, on their very first night in Boone City, all three end up at Butch's. Stephenson drags his concerned but supportive wife, Milly (a radiant Myrna Loy), and eager daughter, Peggy (Teresa Wright, returning from Mrs. Miniver), out for a night on the town, because he can't sit still at home, and they end up at Butch's, with Stephenson so drunk that he thinks he's abroad. Derry wanders into Butch's, because Marie (Virginia Mayo), the wife he married twenty days before shipping out for Europe, has taken a job at a nightclub, but Derry doesn't know the name and can't find her. And Homer takes refuge at his uncle's, because he can't stand his family staring at (or staring away from) the hooks that have replaced his hands. This impromptu gathering at Butch's isn't how any of these men imagined their first night home, but it is emblematic of the challenges that each of them will face in the days ahead. Homer no longer has to work, thanks to regular disability payments from Uncle Sam, but his challenge is to forge a new identity to accompany his altered body. In an effort to spare himself from the pity of others, Homer withdraws from everyone, which threatens the love of the childhood sweetheart, Wilma (Cathy O'Donnell), who waited for him all these years and doesn't seem to care about his prosthesis. As Stephenson cannily observes when Homer exits their cab, the Navy may have done a good job training Homer how to use his hooks, but "they couldn't train him how to put his arms around his girl". Only Homer can do that. Stephenson works to reconnect with Milly and the two children, Peggy and her brother, Rob (Michael Hall), who have become young adults in his absence. Wyler is said to have staged Stephenson's first encounter with Milly to match his reunion with his own wife when he returned from the war. Fredric March and Myrna Loy provide a sophisticated and adult portrait of a long-time married couple who are determined to work together toward re-establishing normalcy. Milly Stephenson's assistance becomes critical, as her husband, a banker, faces conflicting loyalties at work. His boss, Milton (Ray Collins, familiar to Perry Mason fans as the dogged Lt. Tragg), puts him in charge of veteran loans, with the expectation that Stephenson's old reflexes will kick in to deny most of them, despite government assurances. But Stephenson judges people by different criteria since the war. The scene in which, much the worse for drink, he gives a speech on the subject at a bankers' banquet and nearly goes off the deep end, but is restrained by a timely cough (and meaningful stares) from Milly, is a masterpiece. Derry finds himself doing what he swore would never happen, working his old job as a soda jerk at a drugstore that has now been acquired by a national chain that pays him less. Having become accustomed to a life of commitment and responsibility, he wants something more, but his skills as a bombardier don't qualify him for anything in civilian life. If Derry is unsatisfied, Marie, the floozy he married in a rush of pre-war enthusiasm, is even more so. She married a man in a fancy uniform, not a working stiff with a lousy job. The marriage deteriorates rapidly, with additional pressure from the inconvenient fact that Derry and young Peggy Stephenson have fallen for each other since they first met at Butch's—or, more precisely, the next morning, when Derry woke up at the Stephenson home with only a vague recollection of the previous evening. Al and Milly Stephenson are greatly troubled when Peggy confides her feelings and announces her intention to "split up" Fred and Marie Derry, and the result is a memorable scene where her parents give Peggy a tough lesson on the realities of marriage. In one of Best Years' most haunting visual sequences, Fred Derry wanders through the field of planes that he and his two comrades spotted from the air, except that now they're being broken apart for scrap. (The sequence has a documentary feel, because it was filmed in a real air field in Ontario, California.) Derry eventually climbs into a cockpit like the one from which he used to drop bombs and recalls a catastrophic mission that still haunts his dreams. Is he reliving a trauma or returning to better days, a time when he was thought valuable and awarded medals and his life still had meaning? Maybe some of both, because maybe those two things are one and the same. The title "The Best Years of Our Lives" captures an essential ambiguity. The war may have stolen away vital time, golden opportunities and, in the case of Homer Parish, flesh and bone from those who fought it, but it also bestowed clarity, purpose and a sense of self-worth that vanish immediately in civilian life. Almost as soon as they return, they have to deal with murkier problems like (in Homer's case) the gawking of strangers and the pity of family, or (for Stephenson) mercenary concerns that interfere with basic judgments about character, or (with Derry) the sense of futility that leaves a decorated hero adrift and wandering among ruins, looking for answers from fellow citizens who don't even understand the questions being asked.

The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

The cinematographer for The Best Years of Our Lives was Gregg Toland, famous as Orson Welles's collaborator on Citizen Kane, whom Wyler called "a great and happy influence on my work". Some have suggested that it was Wyler who pioneered the technique of "deep focus" photography often credited to Toland and Welles, but it's probably more accurate to say that all three shared the same dramatic impulse to show an audience multiple characters in sharp focus, acting and reacting in different planes within the same frame. The result helps create an illusion of depth. It also, as Wyler pointed out, lets the audience "do its own cutting" by choosing where to look—and makes the close-up more powerful, when it's used. In Virginia Mayo's introduction (listed below under "Special Features"), she refers to the "restoration" of Best Years, but that interview dates back at least fifteen years. No information was available about additional restoration efforts for this new Blu-ray (presented, as per Warner's usual standard in 1080p with AVC encoding), but the results are impressive. Blacks are solid, contrast is appropriately set, and shades of gray are finely delineated. The source material is in excellent shape (or has been well restored) so that there are no specks, scratches or dust. Only an occasional jump indicates a missing frame. Sharpness and detail are somewhat inconsistent. Most of the film is nicely detailed, but some scenes are noticeably softer. There does not seem to be any particular pattern to which scenes are softer; this is certainly not a case where the variation can be explained by the presence of opticals. For example, when Derry walks through the field of airplane scrap, the scene is noticeably less sharp until Derry reaches the bomber where he pauses and climbs into the cockpit; then the detail immediately improves. Some of the early scenes, especially those involving Fredric March and Myrna Loy are notably less detailed than their later scenes, for no obvious reason. Some of the inconsistencies may be inherent to the original photography, while others may be a result of the restoration process. As we know from other restorations performed for Blu-ray, if portions of Best Years had to be supplied from sources of lesser quality, even the most skilled digital massaging could not completely disguise variations in quality. However, without definitive information from the technical crew, it is impossible to know for sure. What can be observed is that the film's grain structure appears to be natural and unfiltered, that the softness is specific to individual scenes and that care seems to have been taken in creating smooth transitions between sequences. Whatever inconsistencies may exist in the source material, they have been handled with care. With scant extras, this nearly three-hour film has an average bitrate of 25.96 Mbps, which has proven adequate for major actions films, let alone a black-and-white drama. Compression artifacts are not an issue. The Best Years of Our Lives has been translated beautifully to Blu-ray.

The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

I have seen references to a stereo mix for the Westrex system, but they are either a mistake or that mix did not survive. The film's original mono mix is presented as lossless DTS-HD MA 1.0, and it is about what one would expect for a well-preserved dramatic film of the era. The voices are clearly reproduced, and the sound effects are natural and well-mixed. Wyler was reportedly not pleased with Hugo Friedhofer's score, even though it won one of the film's seven Oscars, but Friedhofer was producer Goldwyn's pick. There are certainly moments in the film when one might wish for a less sentimental musical accompaniment, but I suspect that Friedhofer's more traditional approach was a major factor in the film's popular appeal. The orchestra doesn't have the clarity or dynamic range of a contemporary recording, but the quality of the Blu-ray track is appropriate to the period.

The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

The Best Years of Our Lives has had several DVD versions. HBO issued the film on DVD in 1998 with the same collection of extras included here. Three years later, MGM released a separate edition with no extras except a trailer (and, as was MGM's habit in those years, a "collectible booklet"). No new extras have been created for the Blu-ray.

- Introduction by Virginia Mayo (480i; 1.33:1; 1:10).

- Interviews with Virgina Mayo and Teresa Wright (480i; 1.33:1; 7:22): The actresses are interviewed separately, and one wishes for more, because what they have to say is enlightening. Wright's observation that she never saw Wyler more relaxed on a set is particularly intriguing.

- Theatrical Trailer (480i; 1.33:1; 1:48).

The Best Years of Our Lives Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

The Best Years of Our Lives was a huge box office success when it was released in November 1946, at a time when the events it depicted were still playing out across the country. Probably no one would have predicted that it would still remain as current as it has. Early in the film, Al Stephenson's son, Rob, tells his newly returned father that one of his teachers says there won't be any more wars, because the risk of annihilation is too great in the nuclear age. That was certainly the thinking for some years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but with the beginning of the Korean War in 1950, the understanding began to shift. Today, after Vietnam, two wars in Iraq and one in Afghanistan (just to name the major U.S. conflicts), we know that the advent of nuclear weapons did not render conventional warfare obsolete, and neither did automation. The issues explored in The Best Years of Our Lives may now play themselves out in a world transformed by technology, social changes, and economic shifts, but their human dimensions remain fundamentally the same. Wyler and his superb cast captured these tensions in a drama that still resonates. Highly recommended.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Mrs. Miniver

1942

The Messenger

2009

Wings

1927

Coming Home

Reissue

1978

From Here to Eternity

1953

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

1943

Love and Honor

Love & Honor

2013

The Edge of Love

2008

The Caine Mutiny

1954

The Bitter Tea of General Yen

1933

Casablanca 4K

80th Anniversary Edition

1942

A Farewell to Arms

1932

Dishonored

1931

The Reader

2008

War and Peace

1956

Blood on the Sun

1945

In the Land of Blood and Honey

2011

The Big Parade

Warner Archive Collection

1925

From the Terrace

Limited Edition to 3000

1960

A Matter of Life and Death

1946