Strike Blu-ray Movie

HomeStrike Blu-ray Movie

Стачка | Stachka | Remastered EditionKino Lorber | 1925 | 88 min | Not rated | Aug 30, 2011

Movie rating

7.5 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 4.5 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

Overview

Strike (1925)

In Russia's factory region during Czarist rule, there's restlessness and strike planning among workers; management brings in spies and external agents. When a worker hangs himself after being falsely accused of thievery, the workers strike. At first, there's excitement in workers' households and in public places as they develop their demands communally. Then, as the strike drags on and management rejects demands, hunger mounts, as does domestic and civic distress. Provocateurs recruited from the lumpen and in league with the police and the fire department bring problems to the workers; the spies do their dirty work; and, the military arrives to liquidate strikers.

Starring: Maksim Shtraukh, Grigori Aleksandrov, Mikhail Gomorov, Ivan Klyukvin, Aleksandr AntonovDirector: Sergei Eisenstein

| Foreign | Uncertain |

| Drama | Uncertain |

| History | Uncertain |

| Period | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.34:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.33:1

Audio

Music: LPCM 2.0

Subtitles

None

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region free

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 4.5 | |

| Video | 4.0 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 2.0 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

Strike Blu-ray Movie Review

Still striking.

Reviewed by Casey Broadwater August 29, 2011“Montage” is definitely one of the most devalued words in the great glossary of cinematic terms. After all, when you hear the word now, you’re probably more likely to think of the fist-pumping, Dolph Lundgren vs. Sylvester Stallone “training” section of Rocky IV than the masterful “Odessa Steps” sequence in 1925’s The Battleship Potemkin. Yes, montage can be a way to quickly show the passage of time, but that’s only one use. Potemkin director Sergei Eisenstein—who, along with D.W. Griffith, practically invented many of the precepts of modern film editing— saw montage as an intellectual tool capable of visually representing a Hegelian, thesis + antithesis = synthesis dialectic. By juxtaposing and intercutting between two unrelated images, he found that he could elicit from his audience a third mental picture, meaning, or emotion. “Montage is conflict,” he once said, and Eisenstein employed his theories of editing to explicitly didactic ends as illustrations of his Marxist ideals, celebrating the class-warfare of the Russian Revolution in his first three films, Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October. While this thematic trilogy was never exactly the rousing, international call to arms Eisenstein hoped it would be, he succeeded in introducing the world to some truly revolutionary ideas about filmmaking.

Strikers

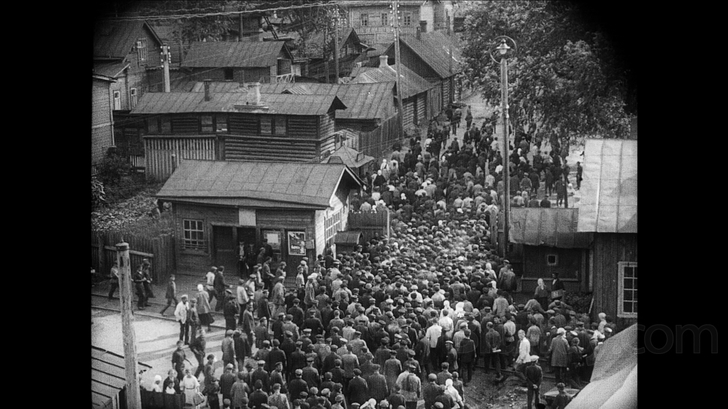

Strike opens with a quote from Lenin: "The strength of the working class is organization. Without the organization of the masses, the proletariat is nothing. Organized, he is everything. Being organized means unity of action, the unity of practical activity." The phrase “unity of action” stands out as Strike’s guiding narrative principal. To merge form and propagandistic function, Eisenstein—in alignment with his Marxist philosophy—eschewed an individual protagonist in favor of a collectivist hero: the proletariat workers en masse. There are no real identifiable “leads,” no central instigating characters—a first in cinema. Instead, the group acts almost like a single organism with a unified purpose: fomenting revolt.

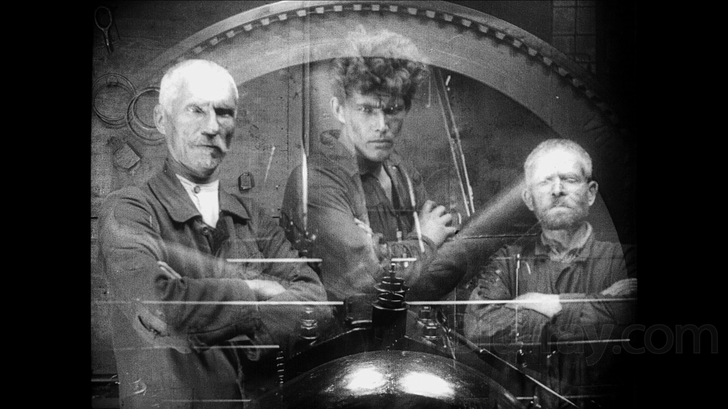

The six-part propaganda film is set in and around a factory in pre-Revolution Russia, where tsarist, capitalist industry owners—all played by fat, sweaty-looking men who sit around drinking cocktails and smoking big cigars—exploit their workers for long hours with little pay. In the first section, we see the workers whispering to each other in silhouette and meeting secretly in the factory restroom to discuss the possibility of a strike. The managers, however, have a cadre of secret agents with animal code names—The Fox, The Owl, The Bulldog, etc.—who have been paid to go undercover and ferret out the insurgents. (When introducing these characters, Eisenstein cleverly fade transitions between the men and the animals they personify.) A strike seems imminent, but it needs a catalyst.

The spark comes when an innocent worker, accused of stealing a micrometer and unable to bear the shame of being labeled a thief, hangs himself inside the factory—an intense scene that seems quite graphic for its time. Here we get one of the first examples of Eisenstein’s correlative inter- cutting; the worker’s leather belt, a makeshift noose, is clearly compared to the system of straps and pulleys that criss-cross the main room of the factory, implicating the workplace in the man’s death. As in Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, which was certainly influenced by Strike, we get the sense of the factory as an impersonal, unnatural, alienating place, and Eisenstein later contrasts this with the pastoral calm of the men’s homes, where he shows us symbols of natural life—playing children, baby chicks, wide-eyed kittens.

The suicide sets off a mass exodus of workers from the plant, and what follows is a series of tableaus that illustrate the up-and-down phases of the strike. At first, the men enjoy their workless lives by spending time with their families, but reality sets in when the factory owners refuses to meet the strikers’ meager demands for an 8-hour workday, fair treatment, and a 30% pay increase. As the strike drags on, starvation becomes a real concern for the poor workers, while in a world apart, Eisenstein gives us images of the grotesque, champagne-swilling decadence of the upper class. Later, the boot-polishing tsarist police are called in to threaten and intimidate, hanging dead cats around the neighborhood and hiring violent, rabble- rousing hobos to mix in with the otherwise peaceful strikers in order to justify an all-out attack.

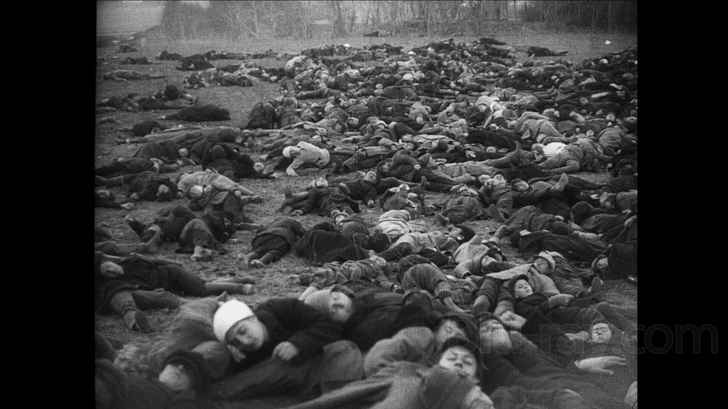

This attack is Strike’s most memorable and influential sequence. As the workers flee from the village and are gunned down by the police out in the fields, Eisenstein flashes to unrelated shots of cows being mercilessly slaughtered, their throats slit and their eyes rolling lifelessly back into their heads. The images are disturbing—PETA members might want to look away—and they serve to make the clear comparison that the workers are treated like cattle, butchered once they’ve outlived their usefulness. This metaphorical cross-cutting technique was unprecedented in its time, but it’s since become part of the established cinematic vernacular, with Eisenstein especially influencing 1970s auteurs like Francis Ford Coppola and Sam Peckinpah. In tribute, Coppola even quotes liberally from Strike in the finale of Apocalypse Now, where Colonel Kurtz is hacked down like a sacrificial bull.

Strike ends with an admonishment to “Remember the Proletariat,” making the film a kind of rousing, “bolster the troops” elegy for those that suffered injustice before the Revolution. Like most propagandistic art from the early 20th century, it’s quaintly didactic and one-sided, which robs it of any real dramatic power today. Still, Strike is a wonder of form and style and editing, and in many ways it seems more modern than just about anything you’d catch at the multiplex this year.

Strike Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Restored by The Cinémathèque De Toulouse and given a 1080p/AVC-encoded transfer by Kino-Lorber, Strike's Blu-ray presentation renders obsolete every prior home video edition of the film. If you own Kino's 2010 release of Battleship Potemkin you'll have a good idea of what to expect—an image that's beautifully resolved, tonally balanced, and faithful to source, free from digital tampering and compression/encode issues. Of course, since the film is nearly 90 years old, there's bound to be some age-related damage to the print. Specks and small pieces of debris often dot the image, brightness fluctuates on occasion, and there are vertical scratches that sometimes run through several seconds of footage, but this is all to be expected from a silent film from the mid-1920s. What's important is that the restoration efforts of The Cinémathèque De Toulouse clearly focused on gathering the best possible materials and presenting them faithfully. The film's inherent grain is fully intact—there are no leftover traces of noise reduction—and edge enhancement doesn't appear to have been used. The level of clarity is often astounding, with strong detail visible in the factory environments and in the gaunt, proletarian faces of the non-professional actors Eisenstein was fond of casting. The tonal gradation is excellent as well, with dense blacks, crisp whites and natural-looking contrast. There are some shots where whites seem a bit blown out, but I suspect this has more to do with the source footage than with any post-telecine digital color grading. This is almost certainly the best the film has looked since its 1925 debut.

Strike Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Strike features a newly commissioned musical score compiled and performed by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, and presented via a Linear PCM 2.0 stereo track. The orchestral music is rich and vibrant, with deep cellos and shimmering strings, bright horns and mournful clarinet. Complementary rather than overpowering, the score suits the film well, underscoring the action and hitting all the right emotional cues, especially during the bleak ending. A 5.1 audio option would've been nice, but I actually prefer a 2.0 presentation for silent films—it feels more appropriate, somehow. All intertitles are in English, and there are forced English subtitles for certain text-heavy shots, like headlines or signs.

Strike Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

- Glumov's Diary (1080p, 4:43): Eisenstein's first film, a playful experimental short made for his stage production of Alexander Ostrovsky's Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man. You can see him warming up here for some of the editing techniques he would establish in Strike.

- Eisenstein and the Revolutionary Spirit (1080i, 37:10): Film historian Natacha Laurent discusses Eisenstein's films in the context of the communist revolution and contemporary Soviet filmmaking.

- Battleship Potemkin Trailer (1080p, 1:32)

Strike Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

Kino-Lorber's consistent output of newly restored silent classics is a true gift to film lovers/collectors. They've done it again with Sergei Eisenstein's debut feature, Strike—made when he was just 26—an energetic piece of "remember the proletariat" propaganda that established the director as one of the key figures in post-Revolution Russian cinema and vastly expanded the visual language of movie editing. The Cinémathèque De Toulouse's restoration of the film is gorgeous in high definition, and the disc also includes Eisenstein's first experimental short, Glumov's Diary, and a wonderfully informative interview with film historian Natacha Laurent. Highly recommended!

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Battleship Potemkin

Броненосец Потёмкин / Bronenosets Potyomkin

1925

Of Gods and Men

Des hommes et des dieux

2010

The Confession

L'aveu

1970

City of Life and Death

南京!南京! / Nanjing! Nanjing!

2009

Cemetery of Splendor

2015

Coup d’état

戒厳令

1973

In the Fog

V tumane

2012

Loveless

Нелюбовь / Nelyubov

2017

The Battle of Algiers

La battaglia di Algeri

1966

Peppermint Candy

박하사탕 | 4K Restoration

1999

Aquarius

2016

A Taxi Driver

택시운전사 / Taeksi woonjunsa

2017

No

2012

Confucius

孔子 / Kong zi

2010

Che: Part Two

2008

Assassination

2015

El Norte

The North

1983

The Club

El Club

2015

Pioneer

Pionér

2013

Alexander Nevsky

Александр Невский / Aleksandr Nevskiy

1938