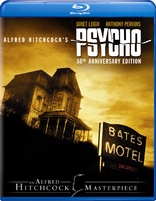

Psycho Blu-ray Movie

HomePsycho Blu-ray Movie

50th Anniversary EditionUniversal Studios | 1960 | 108 min | Rated R | Oct 19, 2010

Movie rating

9 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 5.0 | |

| Reviewer | 4.5 | |

| Overall | 4.7 |

Overview

Psycho (1960)

A Phoenix secretary embezzles $40,000. On the run she checks into the remote Bates Motel, run by a young man under the domination of his mother.

Starring: Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Janet Leigh, Martin BalsamDirector: Alfred Hitchcock

| Horror | Uncertain |

| Mystery | Uncertain |

| Psychological thriller | Uncertain |

| Thriller | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: VC-1

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 (48kHz, 24-bit)

English: DTS Mono

French: DTS 2.0

Subtitles

English SDH, French, Spanish

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region free

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 5.0 | |

| Video | 4.0 | |

| Audio | 4.5 | |

| Extras | 4.0 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

Psycho Blu-ray Movie Review

Norman, is that you?

Reviewed by Jeffrey Kauffman October 6, 2010Note: It’s next to impossible to discuss ‘Psycho’ without revealing the twists of the film. If you’ve never seen the movie, don’t read this review just yet. Either skip to the Video, Audio and Supplement sections, or better yet, just click the ‘Pre-order/Buy Now’ button up above, watch it, and then come back.

Two iconic directors took enormous risks in 1960, entering into the tortured psyches of two very disturbed individuals. Alfred Hitchcock saw his career receive a huge shot in the arm courtesy of Psycho. Michael Powell saw his virtually end with the release of Peeping Tom. The two films are often mentioned in the same breath, as they both have an air of sexual depravity that was still rather rare in that quaintly prim and proper era which was still officially presided over by Eisenhower on this side of the pond, and Harold Macmillan “over there.” So why the disparate responses? What was it about Peeping Tom that offended so many people so deeply, while they were simultaneously thrilled beyond measure by Psycho? After all, both films involve a madman who murders women; if Peeping Tom simply had more notches on its murderous belt, can that be the only reason? Especially when Psycho’s anti-hero also manages to kill at least one man? There’s no getting around the fact that Peeping Tom’s focus, Mark Lewis, also ups the ante by filming his murders, and that, along with the tangential issues of child abuse in the Powell film, probably helped to make it the cause célèbre it became (and not in a good way). The fact that Powell makes the audience the killer, as it were, forced to look through Lewis’ lens as he offs one comely lass after another may have shattered the safe and cozy fourth wall too completely for Powell’s self-reflexive ideas to ever get past the shock.

Hitch's cameo in 'Psycho'.

But there’s another, perhaps more subtle, reason that Psycho was such a sensation (in a good way) in its day, and has continued to be one of the most iconic horror films ever made. Think about this for a moment in terms of modern day horror films: the “villain” of the piece, as oddly lovable as he is, doesn’t show up until 28 minutes into the film. Twenty eight minutes! And then, we don’t get the first, iconic murder until a good 20 minutes after that. Can you imagine a contemporary filmmaker taking their time like that with a modern slash and dash outing? It’s Psycho’s almost somnambulant pace which, while first confounding critics (if not audiences, who were rapturously involved from day one), is Psycho’s trump card. Never before (and far too infrequently since) had a thriller taken its time the way Psycho did, with a long a prelude, including an unusually large amount of static shots, which lulled the audience into a state of (false) security, making that epochal shower scene all the more visceral. Powell started his Peeping Tom with a murder, in fact a “first person” killing that made the audience a participant in the mayhem, willing or not, and it may have been a fatal mistake from a marketing if not an artistic standpoint. Hitchcock, ever the reserved objectivist, stood back, looked at a situation developing, and then calmly and clearly depicted his mayhem with a coldly clinical, surgical (no pun intended) detachment which made the imagery all the more gut wrenching. And since he had let the film breathe for so long before that sequence, the audience was ensconced for the ride, this time quite willingly. (It’s also fascinating to contrast the way the two directors depict the eye in their film: Powell shoots the orb either straight on, or, more frequently, implies that it exists by making the camera provide point of view shots. Hitch, in a startling close-up relatively early in the film when Perkins’ Bates spies on Leigh’s Crane in her hotel room, shoots the eye from the side, maintaining an eerie objectivity).

Psycho is one of those films which has so entered the public consciousness that even people who haven’t actually seen the film feel like they have. But newcomers to this rather odd outing in Hitch’s oeuvre, especially those raised on the quick cut (pun intended) edits of modern horror films, almost always find the opening sequence, full of long, lingering shots of Marian Crane (Janet Leigh) planning a heist and driving into the California desert, either boring or bewildering. Isn’t this film supposed to be about a cross dressing maniac who slices and dices women while they shower? It’s a testament to Hitchcock’s craft that he so carefully prepares the carnage that is to come with this spacious opening act, one which ever so slightly subverts the tamped down, “normal” life of late 1950s America. Here is Marian Crane, “dutiful” secretary, seemingly your typical everyday all American woman, stealing scads of money and then getting the hell out of Dodge before anyone notices.

But so much about Psycho is contrary both to societal expectations, and also Hitch’s typical reverence for the ice cool blonde. In film after film, Hitch iconizes the unreachable, Goddess-like heights of stars like Grace Kelly or Eva Marie Saint. In Psycho, the blonde is furtive, if still cool as a cucumber, and she isn’t just reached, she’s penetrated in one of the most shocking sequences ever caught on celluloid. It’s as if Hitchcock was finally coming to terms with his own perhaps sexually sadistic proclivities, for right or for wrong, and was “letting it all hang out,” at least in this single, solitary instance. (It’s interesting to note Hitchcock was back in “true form” with The Birds, his next film, with perhaps the iciest blonde in his entire filmography, Tippi Hedren). The audience, after having been coddled into its comfort zone, is left then, some 48 minutes into Psycho, without its putative star, wondering what is going on and what possibly could be coming next.

But Psycho is subversive from virtually its first frame, both within the Hitchcock oeuvre and also from an “extracurricular” perspective. Suddenly, the flowing minimalism of Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo score (a minimalism which presaged Philip Glass’ by several decades) has been transformed into the stingingly bitter and fragmented strings of Psycho. After yet another superb Saul Bass title treatment, we open on a nice wide pan of Phoenix two weeks before Christmas, and then slowly move in to an interior hotel shot where we find Janet Leigh and John Gavin, very nearly in flagrante delicto. Films were certainly on the cusp of becoming more sexually frank by 1960, but it was almost always within the confines of amped up glossy emotionalism like Douglas Sirk provided. Here, caught in the lens of John L. Russell’s no frills yet incredibly evocative black and white cinematography (Hitch used his television series crew for Psycho, another innovation), we’re privy to a very “real” looking dalliance between an unmarried secretary and a divorced man who can’t quite commit. This is most certainly not the standard ice cool unapproachable blonde of Hitchcock’s canon.

As Joseph Stefano mentions in the excellent Making of documentary which accompanies the main feature on this Blu-ray, perhaps Psycho’s most enduring piece of subversion, one which has been aped countless times since and was famously parodied in the Scream series, is letting the audience “connect” with whom they think is the star, and then suddenly killing that character and revealing that the film is really about someone else entirely. The fact that that slow realization dawns on the audience after the shockingly brutal shower scene, in yet another insanely languid, almost ten minute sequence, as Norman cleans up and disposes of Marion’s body, is yet another sign of the genius both Stefano and Hitchcock employed in structuring the film. Also pay close attention during the sinking of the car; Hitchcock can’t refrain from introducing one scary-funny moment which is perfectly redolent of his off kilter sense of humor.

Once the film moves into its cat and mouse second act, it may well indeed become a bit more formulaic than the incredibly innovative opening hour or so, but that doesn’t keep Hitchcock from employing a variety of brilliant effects, and Stefano and the actors from offering some amazingly brilliant moments. From the dizzying straight down shot when Martin Balsam (as a private investigator trying to locate Marion) meets “Mother,” which moves into the crazy tracking shot down the stairs, to the final reveal after Marion’s sister Lila (Vera Miles) decides to explore the Bates mansion, this is simply superior, if often extremely subtle, filmmaking at every level. Hitchcock isn’t above using some of his own tropes during all of this. Part of the unease the audience feels in the final showdown is due to the fact that our spunky heroine, Lila, is out on her own in very dangerous territory, much like Grace Kelly’s character in Rear Window when she ventures into Raymond Burr’s apartment all by her lonesome.

Hitchcock was forced to add the sort of silly coda after the denouement, where Simon Oakland as a psychiatrist becomes “Moishe the Explainer” and informs the audience of what exactly was going on all this time. It’s fascinating, though, to once again see Hitchcock (and Stefano) push the filmic envelope of the era by openly discussing transvestitism, something that certainly would have made many in the audience blush over back in those days. And of course Hitchcock wraps the film up beautifully with the final monologue (voiced by Jeannette Nolan) by “Mrs. Bates.” Pay very close attention to Norman’s face right before the dissolve to Marion’s car being hoisted from the swamp to see a little sleight of hand Hitchcock introduces just to get one final “jab” in. (And, yes, that’s none other but an uncredited “Ted Baxter”—Ted Knight—as the policeman opening the holding room door).

Hitchcock had some peculiar ups and downs from Vertigo onward in his career. Vertigo is perhaps his most personal (if oddly objectified) film about obsession and image, a testament to the director’s own Ego, but there has probably never been a more Id-inflected film than Psycho, one which calmly, almost surgically, delves into the depths of human depravity without blinking once. The fact that Psycho is such an oddly calm film is perhaps its most disturbing element in the long run.

Psycho Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Once again, Universal doesn't know quite how to handle its catalog product. While Psycho showers its way onto Blu-ray with an at times startlingly clear and well defined VC-1 encoded 1080p image (in 1.85:1), there are unfortunately some persistent artifacting issues to report. First the good news. For once, Universal doesn't seem to have manically digitally scrubbed their source elements, so grain is still apparent, though not overwhelming. Contrast is for the most part excellent, with an appealing array of gray shades and clearly defined whites and blacks. Clarity is very good, with fine detail pleasing. What hobbles this transfer are a number of very noticeable instances of shimmer, aliasing and other resolving issues, typically on patterns. You'll notice it right off the bat as the camera moves in toward the hotel room window where Leigh and Gavin will soon be revealed. Keep your eye on the bottom of the venetian blinds and you'll quite clearly see artifacting in the close knit parallel lines. Later, when obnoxious businessman Tom shows up at Marion's office and sits on her desk, his crosshatched suitcoat virtually pops off the screen, and not in a good way, as the Blu-ray can't quite deal with all the busy patterns. At the Bates Motel, we once again get some relatively minor shimmer on the plants around the Bates home, which in one shot comes very close to devolving into digital noise territory. These are all transitory issues and don't ultimately rob the film's image of substantial enjoyability, but they will bother the more persnickety videophiles who pick up this release. There's no arguing with the fact that there is certainly an uptick in sharpness and contrast from the previous SD-DVD releases, but Universal needs to take some lessons from Warner in the catalog release department, and go that extra mile in delivering solid transfers.

Psycho Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

I'll admit it, I'm usually not a fan of repurposed 5.1 mixes for films that don't really call for them, so take my comments on this lossless DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix with that in mind. Psycho is, not to state the obvious, a very intimate film, one which gets so up close and personal with its subjects so as to make the audience squirm a great deal of the time. That means the original sound design of the film was often claustrophobic and intentionally narrow. Selecting discrete effects and pasting them in a side or rear channel just seems a little silly to me, but your mileage may vary. That said, the remixers here have not gone over the top in their redesign (which is frequently the case, unfortunately), so major kudos to them for keeping things relatively subdued. There is some decent immersion on this track in some unexpected moments, such as the torrential downpour in which Marion finds herself as she drives across the desert. Some sound effects nicely gurgle through the surrounds, as in the car sinking segment, or earlier when Marion buys her "new" used car and the passing traffic pans through the soundfield according to each individual car's direction. But overall the 5.1 mix, while sporting excellent fidelity (especially in that iconic Herrmann score, which really pushes the high frequencies), seems largely unnecessary for what this film is attempting to do, however well it happens to be done in this instance (and make no mistake, it is, for the most part, done very well here). There's little to no age related damage on this track, with virtually no hiss and, perhaps surprisingly, no noticeable compression in either the extreme highs or lows. A standard DTS 2.0 track is also included which reproduces the original mono soundmix extremely well, and purists may want to stick to that option.

Psycho Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

Quite a few, but not all, of the most recent 2 DVD set's extras have been ported over to this Blu-ray release:

- The Making of 'Psycho' (SD; 1:34:12) is an incredibly excellent feature length documentary on virtually every aspect of the film's production;

- 'Psycho' Sound (HD; 9:58) is an interesting look at the new technologies employed to isolate discrete elements of a mono sound stem to create a 5.1 experience;

- In the Master's Shadow: Hitchcock's Legacy (SD; 25:58) offers some interesting comparisons of Hitchcock sequences with those in other films, and includes a wealth of interviews with directors like Martin Scorsese and John Carpenter who have been influenced by Hitch;

- Hitchcock/Truffaut (Audio; 15:20), an interesting Psycho-centric snippet from their 1962 interview sessions;

- Newsreel Footage: The Release of 'Psycho' (SD; 7:45) is somewhat misleadingly titled, as this is really a "pressbook on film" for exhibitors, describing the "no admittance after the film starts" policy that made Psycho's original roadshow exhibition such a sensation;

- The Shower Scene (SD; 2:30), offers the iconic sequence with and without Herrmann's riveting score;

- The Shower Scene: Storyboards by Saul Bass (SD; 4:10), an interesting compendium of Bass sketches which helped Hitchcock to plan his setups for the sequence;

- 'Psycho' Archives (SD; 7:48), a collection of publicity still;

- Posters and 'Psycho' Ads (SD; 3:00), including some international versions;

- Lobby Cards (SD; 1:30)

Psycho Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

We got a stellar North by Northwest last year as one of the best catalog Blu-rays offered in 2009. Psycho isn't quite up to the visual standards set by that release, but it's a solid offering that should delight (and scare the pants off) most audience members. This is simply one of those iconic films which must be seen at least once by anyone considering themselves a film fanatic. Very highly recommended.

Other editions

Psycho: Other Editions

Psycho

1960

Psycho

Limited Edition | Iconic Art

1960

Psycho

Pop Art

1960

Psycho

60th Anniversary Edition

1960

Psycho 4K

60th Anniversary Edition

1960

Psycho

60th Anniversary Edition

1960

Psycho

60th Anniversary Edition

1960

Psycho 4K

1960

Psycho 4K

1960

Psycho 4K

60th Anniversary Edition

1960

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Gothika

2003

Sinister 2

2015

The Birds 4K

1963

Child's Play 4K

1988

The Blackcoat's Daughter

2015

Sisters

1972

Identity

2003

Psycho II

Collector's Edition

1983

Sinister

2012

Smile 4K

2022

Secret Window

2004

Deep Red 4K

Profondo rosso

1975

Us 4K

2019

The Thing 4K

1982

Proxy

2013

Dressed to Kill

Unrated Version | Second Pressing

1980

Saw 4K

2004

Triangle

2009

The Shining 4K

1980

Frailty

2001