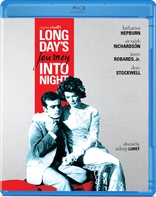

Long Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie

HomeLong Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie

Olive Films | 1962 | 171 min | Not rated | Oct 30, 2012Movie rating

7.5 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 4.5 | |

| Reviewer | 4.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Overview

Long Day's Journey Into Night (1962)

Author Eugene O'Neill gives an autobiographical account of his explosive homelife, fused by a drug-addicted mother, a father who wallows in drink after realizing he is no longer a famous actor and an older brother who is emotionally unstable and a misfit. The family is reflected by the youngest son, who is a sensitive and aspiring writer.

Starring: Katharine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson (I), Jason Robards, Dean StockwellDirector: Sidney Lumet

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Melodrama | Uncertain |

| Period | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio Mono (48kHz, 16-bit)

Subtitles

None

Discs

25GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region A (B, C untested)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 4.0 | |

| Video | 3.5 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 0.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Long Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie Review

A troubling trip definitely worth taking.

Reviewed by Jeffrey Kauffman October 26, 2012This is probably going to strike at least some readers as absolute sacrilege, but as someone with both an English

degree as well as a career that has included substantial work in the theater, I often think Eugene O’Neill’s plays are

better experienced read than actually performed. There’s something about O’Neill’s breathtakingly verbose characters

and his often dour outlook on life that makes experiencing his writing on the stage almost too intense, too

personal, too hard to endure. Reading his plays by contrast allows some distance, as odd as that may seem, as the

action takes place in the reader’s imagination and may therefore not be quite as visceral as when seen before the

eyes. This may be one reason that O’Neill’s plays have not always had an easy transition to cinema, certainly at least

as

vicarious an entertainment as reading or even play going, but also one that envelops the audience in a way that

sometimes cannot be equaled even by live theatrical performances. Seeing an actor in close-up on a huge screen is

obviously a much more intimate experience in its own way than seeing a proscenium stage full of actors, and it certainly

assaults the senses more directly than the reflected image in the mind as one reads. This is obviously a rather

philosophical discussion, but one only need look at some of the films culled from O’Neill’s writing to have some concrete

examples.

One of O’Neill’s first mainstream triumphs, Anna Christie, has been filmed several times, including the

famous version with Greta Garbo that was marketed with the iconic tagline “Garbo Talks!”, but none of the film versions

is able to really capture the full, seedy majesty of O’Neill’s conception. Strange Interlude had to be severely cut

from its original stage

version, not just for length purposes (it ran some four hours in its stage incarnation), but also due to both its explicit

subject matter and its almost nonstop use of soliloquoys, which some productions made more understandable by

having the actors carry masks which they kept aimed at other players on stage while they delivered their “inner

thoughts”. The film version of The Emperor Jones radically reinvented

O’Neill’s conception, even if it kept original Broadway star Paul Robeson, but it often seems shockingly offensive to

politically correct minds when viewed today, and as incredible as Robeson's long monologue is, it's not particularly

cinematic.

One of O'Neill's most titanic accomplishments, Mourning Becomes Electra, was a notorious

flop for RKO and suffered from the fate that seemed to hamper many O'Neill translations from stage to screen: it was

simply too long (over three hours in its original cut, though it was quickly edited down to more manageable size,

something that of course eviscerated O'Neill's text) for contemporary audiences to handle. The case could easily be

made that it was O'Neill's one comedy, Ah, Wilderness!, that actually made the easiest transition to the

screen. (It's perhaps worth noting briefly that both Ah, Wilderness! and Anna Christie have been

musicalized through the years. Ah, Wilderness! actually underwent the transformation twice, as both the 1948

film Summer Holiday and then about a decade later as the Broadway musical Take Me Along!. Anna

Christie hit the stage as New Girl in Town, featuring choreography by Bob Fosse.) All of this of course brings

us to Long Day's Journey Into Night, another one of those legendary O'Neill titles that is characterized by both

its fierce intimacy as well as its perhaps unwieldy length. But due to some very smart direction and a pitch perfect cast,

this is in many ways the most successful film version of any of O'Neill's dramatic pieces.

Lost in the whirlpool of time (something that actually could describe the Tyrone family in this piece) is the fact that Eugene O’Neill wrote Long Day’s Journey Into Night at the height of his powers in the forties, but tucked it away and explicitly stated it was not even to be looked at until 25 years after his death. His third wife managed to get around that issue by giving the play to Yale (even though O’Neill has himself—briefly, anyway—a Princeton man), where it was ultimately published in 1956, three years after O’Neill’s passing. It immediately was recognized as probably O’Neill’s greatest accomplishment, winning the author yet another (posthumous) Pulitzer Prize. The piece is O’Neill’s most unvarnished and disturbing autobiographical writing, a stinging indictment of a family unraveling, beyond mere “dysfunction”, due to incipient substance abuse problems by all of them to one degree or another.

Father James Tyrone (Ralph Richardson) is an aging actor with a drinking problem who has traded craft for monetary gain (something O’Neill’s own father was guilty of having done), though Tyrone has become a notorious skinflint in the process. James’ wife Mary (Katharine Hepburn) is under the nefarious influence of a morphine addiction, something she claims she needs for arthritis but which is obviously her crutch to help her deal with a lifetime of disappointment and in at least one case, a long ago tragedy. The Tyrones have two boys, Jamie (Jason Robards), following in his father’s footsteps as both an actor and an alcoholic, and Edmund (Dean Stockwell), a sweet but agitated young man who shares in his male relations’ fondness for drink but who is dealing with a rapidly deteriorating case of tuberculosis as the film opens.

The film is a slow dance for four characters (only one semi-major character other than the family appears, the Tyrone’s maid, who has one crucial scene with Mary). What is fascinating in O’Neill’s brilliant structuring is how things are a kind of round robin where seemingly every conceivable combination of characters segues in and out of scenes and how everything ultimately references other items in the piece. The fact that the entire outing takes place over the course of one day only makes it all the more remarkable.

This is obviously an actor’s piece and it is undeniably one of Katharine Hepburn’s most commanding performances. She is alternately bitter and tragic, a hopeless (and helpless) drug addict who veers between condemnation of her husband (and at least her older son) and then tearful attempts at reconciliation. There’s an almost incestuous feel at times to the relationship between Mary and younger son Edmund (watch how she caresses him in the first scene on the porch). Through it all Hepburn is absolutely fearless, stripping this character down to its naked, fragile core. The final scene (somewhat different than the play) is a devastating moment of truth veiled as drug fueled dreaming and Hepburn pulls it off immaculately.

Richardson is rather surprisingly the weakest link in this ensemble. He lurches in and out of James’ Irish brogue and he never modulates the character as carefully as he might have. Still, he’s an absolutely commanding presence and his scenes with Robards especially have the ring of truth about them. Both Robards and Stockwell are exceptional as the “boys” (young men, really, and in the case of Jamie, not all that young anymore). Robards’ evinces the sad resignation of Jamie’s character perfectly, and Stockwell manages to play Edmund’s tragic fate without any hint of self-indulgence.

As I mentioned in my review of the Olive release of Sidney Lumet’s 1972 thriller Child's Play, the director excelled at (and indeed seemed to gravitate toward) films with claustrophobic settings. What’s so interesting about his adaptation of the O’Neill opus is that he does in fact open up the play, at least slightly: we get at least a couple of scenes out doors, and we move around the spacious grounds of the Tyrone mansion, something that is not part of the original play. And yet this is in some way the most claustrophobic piece in Lumet’s impressive oeuvre. We are so close to these characters we can almost see beneath their ravaged skins. In fact it’s that very lack of distance, something which I mentioned makes seeing O’Neill more troubling than merely reading him, that gives this film its inherent and undeniable power. This version of Long Day’s Journey Into Night may well be too intense, too personal and too hard to endure, but it is ultimately completely and inescapably unforgettable.

Long Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Long Day's Journey Into Night is presented on Blu-ray courtesy of Olive Films with an AVC encoded 1080p transfer in 1.78:1. While this is easily the best this film has ever looked on any home video release, there are still some issues, most of which are endemic to the elements. I've seen this film projected several times as well as seen previously released DVDs, and even the theatrical exhibitions suffered from inconsistent contrast and some damage, two things that are well in evidence here. There are recurrent (albeit minor) problems at the very edge of the frame, with what looks like print- through or bleed-through running up the sides of the image from time to time. Some of the darker sequences (notably the ending of the film) are hobbled by extremely milky blacks and print-through. Aside from these flaws, however, this is a wonderfully sharp and well detailed transfer that beautifully conveys Boris Kaufman's lustrous black and white cinematography. The film is filled with extreme close-ups, and those reveal abundant fine detail.

Long Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Long Day's Journey Into Night's lossless DTS-HD Master Audio Mono track is in very good shape. O'Neill's poetic dialogue is presented cleanly and clearly, and Andre Previn's spare piano based score sounds surprisingly full bodied (some previous home video releases wreaked havoc with Previn's score, making it a tinny, brittle mess). There's no real damage of any kind to report on this track. This is obviously a very narrow soundscape, but it's artfully rendered, and some of the foley effects, notably the omnipresent foghorn, sound just fine.

Long Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

There are no supplements included on this disc.

Long Day's Journey Into Night Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

Long Day's Journey Into Night remains a lot to digest, and some may not be able to make it through the entire film in one sitting. But this is simply a showcase for its stars, and O'Neill's original conception and writing makes it through virtually unscathed. Lumet directs with understatement, but he extracts one of Hepburn's most compelling performances. This Blu-ray still exhibits some of the anomalies that have hindered every showing of this film, either theatrically or on home video, that I've personally witnessed, but it also features much stronger overall contrast and detail than on previous releases. Highly recommended.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Death of a Salesman

1985

Krisha

Signed Limited Edition to 100 Copies - SOLD OUT

2015

Her Smell

2018

Written on the Wind

1956

Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter

2014

The Ballad of Narayama

楢山節考 / Narayama bushikô

1958

Beanpole

Дылда / Dylda

2019

Europe '51

Europa '51 / The Greatest Love / English and Italian Versions

1952

Mass

2021

The Damned

La caduta degli dei

1969

Factory Girl

2006

Bigger Than Life

1956

The Rocket

2013

Julieta

2016

Diary of a Country Priest

Journal d'un curé de campagne

1951

Elles

2011

Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood

2002

Zama

2017

Olive Kitteridge

2014

Happy End

2017