Howl Blu-ray Movie

HomeHowl Blu-ray Movie

Blu-ray + DVDOscilloscope Pictures | 2010 | 84 min | Rated R | Jan 04, 2011

Movie rating

6.3 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 4.0 | |

| Reviewer | 3.5 | |

| Overall | 3.8 |

Overview

Howl (2010)

It's San Francisco in 1957, and an American masterpiece is put on trial. Howl, the film, recounts this dark moment using three interwoven threads: the tumultuous life events that led a young Allen Ginsberg to find his true voice as an artist, society's reaction (the obscenity trial), and animation that echoes the poem's surreal style. All three coalesce in hybrid that dramatizes the birth of a counterculture.

Starring: James Franco, David Strathairn, Jon Hamm, Bob Balaban, Jeff DanielsDirector: Rob Epstein, Jeffrey Friedman

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Biography | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1

English: LPCM 2.0

Subtitles

English, French

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Two-disc set (1 BD, 1 DVD)

DVD copy

Playback

Region free

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 3.5 | |

| Video | 4.0 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 3.0 | |

| Overall | 3.5 |

Howl Blu-ray Movie Review

And the Beat goes on.

Reviewed by Casey Broadwater January 14, 2011As the most vile, explicitly perverse material is currently only a few mouse clicks away, it’s hard to imagine a time when a poem—a poem!—could cause its publisher to be brought to trial on obscenity charges. And yet that’s exactly what happened in the morally straightjacketed America of 1957, when publisher and City Lights Books owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti was arrested for releasing Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl and Other Poems,” a book initially deemed obscene for its numerous references to sexual—and, in particular, homosexual—behavior. Written in ragged, Walt Whitman-meets-bebop rhythms, the four-part poem—a lament for “the best minds” of Ginsberg’s generation, a critique of industrialized society, and an ode to friend Carl Solomon, the “cocksman and Adonis of Denver”—is not quite as shocking today as it was in the mid-1950s, but it still possesses an incendiary, incantational, almost shamanistic power. Hearing this piece of era-defining free verse read aloud, nearly in its entirety, is the sole source of ecstasy in this otherwise surprisingly un-lyrical new film about the poem, co-directed by Rob Epstein and Jerry Friedman (The Celluloid Closet).

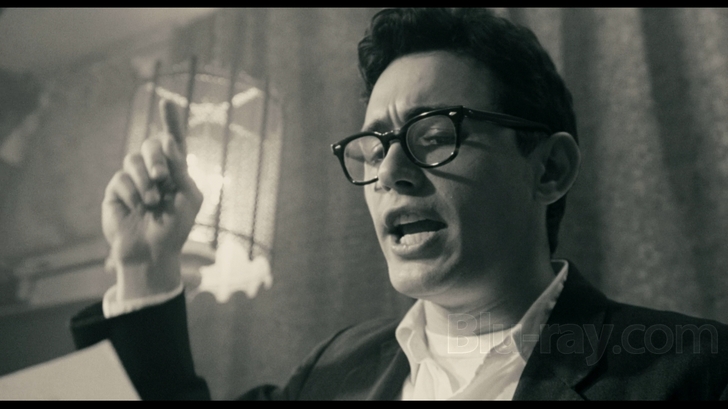

James Franco as Allen Ginsberg

Going into Howl, I was under the impression that it was going to be a fairly conventional biopic—you know the drill—dramatizing each writerly torment and unrequited passion of Allen Ginsberg’s young life. Something close, perhaps, to Sylvia or The Edge of Love, films that writhe around in the muck of their protagonists’ personal lives. But Howl isn’t like that at all. In fact, the film is much closer to an act of creative literary criticism than a traditional and linear biographical narrative. That is, it’s about the poem itself much more so than the poet. While they original set out to make a documentary, Epstein and Friedman eventually settled on an unusual structure for Howl, making it one part reenactment, one part faux-interview, one part recitation, and one part animated phantasmagorical freakout. They begin the movie with the following statement: “Every word in this film was spoken by the actual people portrayed. In that sense, this film is like a documentary. In every other sense, it is different.” This is an ambitious, if not entirely successful tact—since each line of dialogue has been gathered from the public record, the directors force themselves into a rather strict, purely academic interpretation of the story. There’s no room here for speculated conversations, fleshed out flashbacks, or drama of any kind, really; every utterance has been pulled from courtroom transcripts, interviews with Ginsberg, and, of course, the long, breathless lines of the poet’s magnum opus.

The film alternates between several stylistically distinct sequences. In color, we follow the particulars of the Ferlinghetti trial, presided over by Judge Clayton W. Horn (Bob Balaban). Humorless prosecuting attorney Ralph McIntosh (David Strathairn) bases his entire case on trying to prove that “Howl” is not only indecent, but also completely incomprehensible and devoid of any redeeming social or literary merit. He calls to the stand several stuffy scholars—including Jeff Daniels as Professor David Kirk—who all testify to the poem’s inherent worthlessness and lack of “moral greatness.” In retort, defense lawyer Jake Erhlich (Mad Men’s Jon Hamm) argues that Ginsberg is simply documenting the authentic experience of a troubled but gloriously uninhibited subset of the post-WWII American populace. Which he was. And obviously, by illuminating what the majority would much rather keep in the dark—homosexuality and the counterculture at large—Ginsberg scared society’s squares senseless. The poem, the trial, and the attention that the trial inevitably brought to the poem were some of the first salvos fired in the cultural revolution that would challenge the country’s moral center in the 1960s.

Interspersed with these procedural courtroom scenes, we observe Ginsberg—capably played by multi-talented wunderkind and NYU grad student James Franco—at home fielding questions from some never-seen interviewer about the trial, his poetry, and his early life. Occasionally, the film darts back in time to reconstruct portions of the past—Ginsberg meeting Kerouac (Todd Rotondi), bumming around with Neal Cassady (John Prescott), and finally finding love with longtime life partner Peter Orlovsky (Aaron Tveit)—but these reenactments are strangely inert. Since we don’t know what may have been said during any of these encounters, Epstein and Friedman struggle to portray them near-silently, an example of the filmmakers sticking so closely to their rule—to only use authenticated dialogue—that the storytelling suffers somewhat. More effective, and even moving, is when they cut to the smoky black and white poetry reading where Ginsberg first looses his primal “Howl” upon the literary world. Here, Franco shows an uncanny ability to channel the poet’s idiosyncratic vocal mannerisms. As he reaches the poem’s “Footnote,” an epilogue of sorts that repeats the word “holy” like a worshipful mantra, the film very nearly approaches the sublime.

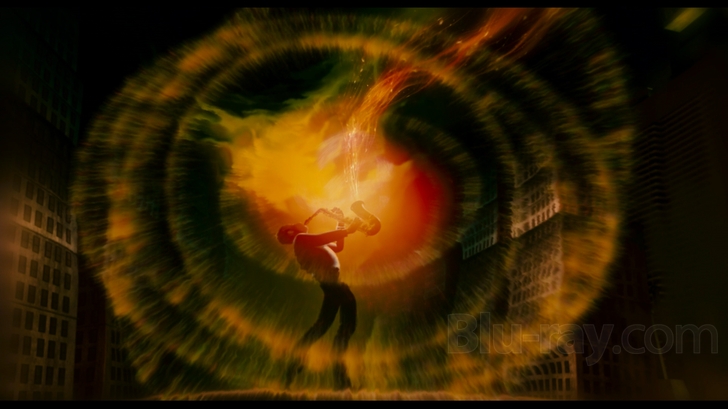

Unfortunately, prior to this, vast stretches of the poem are illustrated with CGI and cel-animated interpretations of Ginsberg’s imagery, suggesting some borderline pornographic mash-up of Disney’s Fantasia and a come-to-life Matisse painting. (With heavy intonations, in the Moloch- centric stanzas of Part II, of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.) For example, when we hear Franco reading one of the more-controversial lines—“who blew and were blown by those human seraphim, the sailors, caresses of Atlantic and Caribbean love”—we witness a tropical jungle of penis-shaped palm trees ejaculating into the sky, where the seminal fluid turns into explosions of glittery fireworks. Elsewhere, “angel-headed hipsters” surrounded by glowing auras toot on saxophones or tumble naked above the cityscape in orgiastic couplings. It’s a bit too obvious and it only serves to dull the impact of Ginsberg’s words. If “you can’t translate poetry into prose,” as one witness for the defense claims—suggesting that “Howl” shouldn’t be subject to a strictly literal reading—what makes the filmmakers think they can translate poetry into a strictly literal graphic form?

Howl Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Oscilloscope Laboratories brings Howl to Blu-ray with a 1080p/AVC-encoded transfer that—if not the sharpest, most vibrant picture you've seen lately—is certainly rich, organic, and likely true to source. The film's four distinct scenarios are all handled wonderfully here. The black and white sections have a strong monochromatic gradation and an appropriately authentic vintage quality. The court case features a realistic color palette with warm wood hues and balanced skin tones, while the at-home interviews with Ginsberg are given a more intense, almost cross-processed color grading. Finally, the animation, as corny as it is sometimes, at least looks good. The image's sharpness isn't exemplary, but there's plenty of refined detail visible in Ginsberg's wool suits and thin, carefully groomed beard. The film's grain structure looks entirely natural and aside from some mild, blink-and-you'll-miss-it banding in a few of the animated sequences, I didn't spot any notable compression issues.

Howl Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Aside from being mastered somewhat low—I had to bump my receiver up about ten notches from my normal listening levels—there's nothing wrong with the film's DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track, which handles the limited requirements of the dialogue-driven mix with ease. The animated scenes understandably have the most going on sonically—with occasional cross-channel swishes and swooshes—although the rest of the film does feature a quiet but appreciable amount of New York City ambience. There's nothing particularly intense or room rattling here, but the jazzy music has plenty of presence, the effects are clear, and the dialogue is always clean and comprehensible. The disc also includes an uncompressed PCM 2.0 stereo mix that works just as well.

Howl Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

- Commentary with James Franco and Directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman

- Holy! Holy! Holy! The Making of Howl (1080i, 40:00): An engaging production documentary that guides through the entire process of making the film and features interviews with just about everyone involved.

- Directors' Research Tapes (SD, 28:32): Interviews with Ginsber's close friends and collaborators, including graphic novelist Eric Drooker, Ginsberg's life partner Peter Orlowsky, poet Tuli Kupferberg, publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and musician Steven Taylor.

- Allen Ginsberg Reads at the Knitting Factory (SD, 35:01): In 1995, Allen did ten shows at the Knitting Factory, where he read several of his poems. Here, we get to hear Howl, Sunflower Sutra, and Pull My Daisy.

- James Franco Reads Howl (audio only, 25:00): Franco reads the poem in its entirety.

- Provincetown Film Festival Q&A (1080i, 22:28): Epstein and Friedman sit down with Shortbus director John Cameron Mitchell, who moderates this discussion about Howl.

Howl Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

While I appreciate Epstein and Friedman's willingness to skirt the traditional biopic form in favor of a hybrid documentary/reenactment, Howl has a few shortcomings that keep it from greatness, most notably its poor, over-literal attempt at turning the poem into an animated graphic novel of sorts. Still, if you're a student of literature, a one-time member of the Beat Generation, or even just a James Franco fan, the film is worth watching at least once. Casually recommended.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

The Master

2012

Factory Girl

2006

Young Mr. Lincoln

1939

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

1960

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

2009

Big Eyes

2014

Cesar Chavez

2014

Wildlife

2018

American Pastoral

2016

Still Alice

2014

Opening Night

1977

Puncture

2011

Kramer vs. Kramer

1979

The Irishman

2019

Mommy

2014

A Taste of Honey

1961

Rebel in the Rye

2017

At Eternity's Gate

2018

Priscilla

2023

Chattahoochee

1989