Freakonomics Blu-ray Movie

HomeFreakonomics Blu-ray Movie

Magnolia Pictures | 2010 | 93 min | Rated PG-13 | Jan 18, 2011Price

List price:Amazon: $8.49 (Save 50%)

Third party: $8.49 (Save 50%)

Only 1 left in stock (more on the way).

Movie rating

6.8 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 3.5 | |

| Overall | 3.5 |

Overview

Freakonomics (2010)

Freakonomics is the highly anticipated film version of the phenomenally best-selling book about incentives-based thinking by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner. The film examines human behavior with provocative and sometimes hilarious case studies, bringing together a dream team of filmmakers responsible for some of the most acclaimed and entertaining documentaries in recent years.

Starring: James Ransone, Bill Gates, Zoe Sloane, Konishiki, Ngozi Jane AnyanwuNarrator: Morgan Spurlock, Melvin Van Peebles

Director: Heidi Ewing, Alex Gibney, Seth Gordon, Rachel Grady, Eugene Jarecki

| Documentary | 100% |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1

Subtitles

English SDH, Spanish

Discs

25GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region A (B, C untested)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 3.5 | |

| Video | 3.5 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 2.5 | |

| Overall | 3.5 |

Freakonomics Blu-ray Movie Review

Taking the omnibus to school…

Reviewed by Casey Broadwater January 19, 2011I read 2005’s surprise economics-meets-sociology bestseller Freakonomics over two lengthy sessions in a chiropractor’s waiting room, and my first impression was that, while the book is enjoyable and contains some provocative ideas, it ultimately comes across as scattershot and a little short. I feel the same way about this new documentary, which will seem completely redundant for those who’ve already read the book. And for those who haven’t, well, you’d probably be better off checking out the slim non-fiction tome from the library than putting the film in your Netflix queue, as the documentary is really just a compressed and illustrated retelling of the concepts and anecdotes that co-writers Steven D. Levitt ("rogue" economist) and Stephen J. Dubner (journalist) introduced us over half a decade ago now. So, who is this film for? I suppose it’s for those who don’t like to read, but I can’t imagine non-readers being terribly interested in experimental economic theory. But who knows? Regardless, arriving five years after Freakonomics’ much blogged-about cultural blitzkrieg, the documentary serves as a primer for those who missed out the first time around.

Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner

So, what is Freakonomics? I read the book and just watched the film, and I have trouble saying with any certainty. If I had to put a finger on it, it would be the use of statistics to debunk misconceived causality—like, say, how doctors in the 1950s thought childhood polio may have been caused by eating ice cream—and the attempt to explore, as the book’s subtitle suggests, “the hidden side of everything.” In one segment of the film, about cheating in sumo wrestling—I’ll get to that in a second—an ex-CIA agent discusses two Japanese words that explain the concept best: Tatamae means “the surface of things,” and honne means “real truth.” Freakonomics, then, might be described as an attempt to get past the tatamae to see the honne of what’s going on around us. The other aspect of this is the ability to predict behavior and outcomes. “People respond to incentives,” says Levitt in one of the joint interviews with Dubner that are interspersed throughout the film. “If you can figure out what people’s incentives are, you’ll have a good chance of guessing how they’ll behave.” At its most general, Freakonomics is a melding of economics, sociology, and marketing, which is nothing new—the three have forever been intertwined—but Levitt and Dubner have a knack for introducing layman audiences to tricky concepts by way of striking, and sometimes bizarre topical examples.

The film version of Freakonomics takes an omnibus format, with each segment—you might call them visual essays—interpreted and shot by a different indie documentary director and tied together with interview footage of Levitt and Dubner explaining the key ideas. Supersize Me’s Morgan Spurlock takes the first sequence, “A Roshanda by Any Other Name,” in which he explores the question of whether a child’s name can determine his or her future success or failure. He gives the real-life example of an unfortunate inner-city girl whose mother, intending to name her after The Cosby Show’s Tempestt Bledsoe, inadvertently calls her “Temptress” instead. Temptress ends up on the wrong side of the law as an adult, but Spurlock—by way of Levitt’s original essay—argues that her name itself isn’t to blame so much as the fact that she grew up in the kind of place where a person would name their kid “Temptress.” This segues into a discussion about society’s perception of typically “white” and distinctively “black” names, and how this signifies the presence of latent racism, or at least a collective tendency to stereotype people based on their names. The sad statistical fact is that an Edward or an Emily has better odds in life than a Delshawn or a Uneqqee, not because of their names, per se, but because of the economic and social class brackets into which children with those names usually fall. This is interesting, but not exactly a revelation.

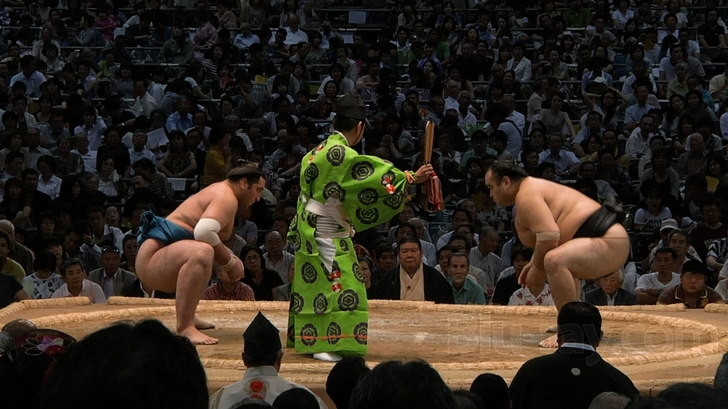

More surprising is the next segment, “Pure Corruption,” Client 9 director Alex Gibney’s exposé on match-rigging in professional sumo wrestling. Japan’s indigenous sport, with its 2,000 year history and ridged symbolic system of purification rituals, would seem like an odd place to find cheating, but Dubner believes that this is precisely why cheating occurs. “I think that purity is a good mask for corruption,” he says, “in that it discourages inquiry.” We learn that for sumo wrestlers to move up in rank, they must win at least eight out of fifteen matches during a tournament. If a wrestler already has eight wins under his belt and he’s going up against a fighter with only seven, he has nothing to lose, whereas his opponent has everything to gain. This has led to a hush-hush custom of fixing matches that’s really only visible if you look for patterns in the raw data. When two ex-wrestlers came forward in 1996 with a tell-all confessional—and then conspicuously died on the same day, in the same hospital—they brought the practice public, which caused a temporary decline in cheating, prompting Dubner to reiterate the old adage that “sunshine is the best disinfectant.”

The film’s third vignette will likely be the most controversial. In “It’s Not Always a Wonderful Life,” Eugene Jarecki (Why We Fight) reveals an unsettling correlation—that the decline in violent crime during the 1990s can be largely attributed to the legalization of abortion in the 1970s following the Roe v. Wade trial. It’s disturbing, in a way, but it also makes sense; a whole generation of potentially unwanted children—the kind most susceptible to getting involved in drugs or violence—were simply never born. Levitt and Dubner have no political or moral ax to swing, they’re just mining the data and bringing it up into the light. Their point is that things aren’t always what they seem.

The closing short asks the question, “Can a 9th Grader Be Bribed to Succeed?” Here, Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (Jesus Camp) follow two young high schoolers as they participate in an incentive program—an experiment initiated by the University of Chicago—that rewards students with $50 a month if they maintain straight C’s or above. The results are rather inconclusive—one of the students improves, while the other does worse— and Levitt argues that while financial motivations definitely matter, students also need more social and moral incentives to do well in school.

As a whole, Freakonomics—the film—feels exactly like what it is, a collection of disparate discussions linked only by a somewhat vague desire to get to the bottom of things. This isn’t necessarily bad; I like that Levitt and Dubner are encouraging people to examine the world around them from all possible perspectives, but I’d much rather watch a feature-length documentary on, say, corruption inside the world of sumo wrestling, than the abbreviated, incomplete overviews we get here. For newcomers to the nascent field of Freakonomics, the film is probably worth 93- minutes of your time, but for those of us who’ve already read the book, what’s our incentive?

Freakonomics Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Shot on high definition video and interspersed with animated sequences, Freakonomics makes the transition to Blu-ray quite easily, with a 1080p/AVC-encoded transfer that may not be particularly cinematic, but is probably true to its source. Each of the vignettes has a slightly different visual style, but aside from some black and white film footage from the sumo wrestling segment, it looks like all of the shorts were shot with the same kind— or, at least, quality—of gear. Clarity is somewhat inconsistent—varying between tack-sharp and moderately soft—but there's never a moment when you'd be convinced that what you're watching is anything less than high definition. Likewise, color is realistic and black levels are adequately dense, although there are some shots that look a bit overexposed. The one oddity I noticed was that the interview segments with Levitt and Dubner are subject to some black haloing along edges—although, whether this is an aftereffect of oversharpening or something inherent in the source, it's hard to say. Regardless, it's nothing to, ahem, freak out over.

Freakonomics Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

The film comes equipped with a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track that delivers exactly what you'd want and hope for this kind of documentary— clear, balanced, effortlessly intelligible dialogue, a moderate amount of immersive ambience, and plenty of punchy music to fill in the gaps. Obviously, there's nothing here as sonically intense as what you'd hear in an action film, but the mix is far beefier than what you'd get in a typical TV documentary. What else is there to say? Oh, right, subtitles—for those that need or want them, English SDH and Spanish subs are available in clean, easy-to-read lettering.

Freakonomics Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

- Audio Commentaries: The disc comes with a bevy of commentary options. Throughout the entire film, you can listen to a track with producers Chris Romano, Dan O'Meara, and Chad Troutwine, but if you go to the special features menu, you'll also find the option to watch each individual segment of the film with commentary by the director(s). There's also the ability to "play all."

- Additional Interviews with Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner (1080p, 37:43): Fourteen additional interviews with Levitt and Dubner, who discuss everything from their definition of "freakonomics" and how they choose what topics they'll broach, to the incentives of hand washing and how to find a good doctor. Worth watching.

- HDNet: A Look at Freakonomics (1080i, 4:46): A typical HDNet "look," part promo, part synopsis, with a few quick interviews.

- Freakonomics Books (text only): Advertisements for the books, basically.

- Also From Magnolia Home Entertainment (1080p, 8:40): A series of trailers for upcoming Magnolia releases.

Freakonomics Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

The movie probably would've fared better had it been released shortly after the massively popular book, instead of trudging out five years later, but for those of you who completely missed out in 2005—and who are inherently interested in all things economic or sociological—Freakonomics is worth checking out at least once. Just pick the book or the film—there's really no incentive to invest time in both.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Fahrenheit 11/9

2018

Whitey: United States of America V. James J. Bulger

2014

Best of Enemies

2015

Dinosaur 13

Director's Cut

2014

Why We Fight

2005

Capitalism: A Love Story

2009

Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room

2005

Inside Job

2010

I Am Chris Farley

2015

The Ambassador

2011

West of Memphis

2012

The Absolute Best of Ghost Hunters

2008

Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich

Deluxe Edition

1958

Icons Unearthed: Star Wars

2022

A Disturbance in the Force: How the Star Wars Holiday Special Happened

2023

Ken Burns: Benjamin Franklin

2022

Cleanin' Up the Town: Remembering Ghostbusters

2019

In Search of the Last Action Heroes

2019

The Queen

1968

Turtle Odyssey 4K

IMAX Enhanced

2018