Film Blu-ray Movie

HomeFilm Blu-ray Movie

Milestone | 1965 | 22 min | Not rated | Mar 07, 2017Movie rating

6.8 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 3.5 | |

| Overall | 3.5 |

Overview

Film (1965)

A twenty-minute, almost totally silent film (no dialogue or music one 'shhh!') in which Buster Keaton attempts to evade observation by an all-seeing eye. But, as the film is based around Bishop Berkeley's principle 'esse est percipi' (to be is to be perceived), Keaton's very existence conspires against his efforts.

Starring: Buster Keaton, Nell Harrison, James Karen, Susan ReedDirector: Alan Schneider, Samuel Beckett

| Foreign | Uncertain |

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Short | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.34:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.37:1

Audio

English: LPCM 2.0 Mono (48kHz, 16-bit)

Subtitles

None

Discs

Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region A (B, C untested)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 3.0 | |

| Video | 4.5 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 3.0 | |

| Overall | 3.5 |

Film Blu-ray Movie Review

Film Review

Reviewed by Michael Reuben March 17, 2017The Irish author Samuel Beckett won the Nobel Prize for Literature for his novels and plays,

including his most famous drama, Waiting for Godot, but Beckett was also fascinated by film. So

much of Beckett's work revolves around the phenomenon of being seen (and not being seen) that

the inherent voyeurism of cinema should have been a natural fit for the writer. Unfortunately,

Beckett's sole venture into filmmaking was not a happy experience. It resulted in a 22-minute

short film that received significant attention in intellectual circles and at film festivals (including

Cannes), not only because of its celebrated screenwriter but also because it starred legendary silent

film star Buster Keaton, whose famous "Great Stone Face" seemed a natural fit for Beckett's

miminalist writing. Ironically, Keaton was far from Beckett's first choice to star in his cinematic

debut, and that disjunction between intent and result is typical of the entire project, which

ultimately disappointed its writer, its star and its first-time director. Reviews were almost entirely

negative, some savagely so.

Beckett's titles were typically short and functional, and he would eventually write a play called,

simply, Play; so it's not surprising that the title he finally chose for his sole venture into film was

Film. But a working title for the project was "The Eye", and with all its flaws, Film represents a

singular effort to express the power of the camera as an instrument of sight. This and related

themes have been explored in depth by film historian Ross Lipman, the driving force behind the

restoration of Film, who became so engrossed in the project that he made a two-hour

documentary about the work and its creation. Lipman's documentary is titled, appropriately

enough, Notfilm. Both

projects have been

released

on Blu-ray by those stalwarts of cinema

history at Milestone Film & Video.

Beckett was an accomplished scholar of literature, language and philosophy, and the often simple surface of his writing is deceptive. Every word is carefully chosen, every nuance thoroughly considered. After an apprenticeship (of sorts) as a secretary to James Joyce during the writing of Finnegan's Wake, Beckett decided to pursue a literary approach that was the exact opposite of his fellow Irish ex-patriate's. Where Joyce's work was the very definition of "more", Beckett would aspire to less. Much of his work can be viewed as a sustained experiment in subtraction from conventional forms. He wrote in French, then translated the works into English, because, as he said, the process ensured that he wrote "without style". In novels, his protagonists become voices without history, family, human relations or, ultimately, names. In drama, he removed all of the familiar accoutrements of character and stagecraft until, in Not I, only an illuminated mouth remained on a darkened stage.

Film attempts a similar approach onscreen. Its protagonist is a man who is never identified (although Beckett dubbed him "O" for "object") and whose face the camera rigorously avoids showing until the end—an ironic twist when Keaton was cast in the part, since his visage is famously iconic. The principal set is a room with only a few furnishings. "O" spends the entirety of Film trying to eliminate the possibility of being seen by any person, animal or thing. It's an inherently futile quest, since it takes place before the camera's implacable eye, which, in the climax of Film, swings around to face "O" and reveal its identity.

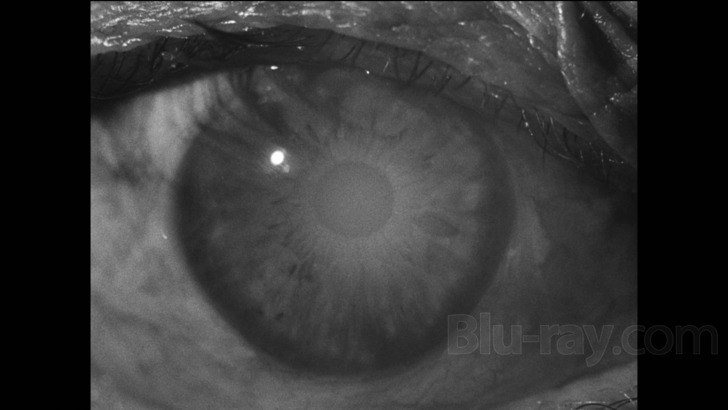

Film opens with a closeup of an actual eye, whose owner is unknown. It then finds "O" in a rubble-strewn exterior, where he encounters several people who recoil in horror when confronted directly with the invisible eye following "O". (One such person is played by veteran character actor James Karen, a long-time friend of Keaton's, who recommended him for the part when the originally cast Jack McGowran, a regular in Beckett's plays, became unavailable.) "O" then retreats to a bare, decrepit room, where he covers mirrors, rips up drawings and photographs depicting figures with eyes, and removes a menagerie of pets who might look at him, including a cat and dog who keep evading his efforts to put them outside. (The last item is Film's most successful effort at humor and, not surprisingly, it was suggested by Keaton.) Even inanimate objects with eye-like configurations—the back of "O's" rocking chair, the closure on a manilla envelope—are inspected skeptically. Having apparently accomplished his task, "O" falls asleep, only to awaken to the "eye" of the camera, which, in a final reveal, turns out to be his doppelganger.

Cinematographer Boris Kaufman (an Oscar winner for On the Waterfront) did multiple tests to create distinct visual styles differentiating "O's" point of view from that of the camera following him. The camera's eye is unwaveringly clear, whereas "O's" vision is blurred and dimly focused. Film has no soundtrack, except for one ironic utterance in which a character says "Shhh!" (Mel Brooks appropriated this gag for Silent Movie, in which the sole audible word is spoken by a mime.) Director Alan Schneider, a theater director making his first film, and editor Sidney Meyers (Edge of the City) do their best to provide a dramatic shape to Beckett's meditation on the power of sight, but Film never attains that unique quality of Beckett's best work, in which conceptual insights are translated into emotion. A masterwork like Waiting for Godot intimates volumes of thought about the essence of being, but they remain outside the drama, informing it without direct expression and conveyed to the audience intuitively. Film never exceeds its philosophical origin. It gives you something to think about, but nothing to feel.

Film Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

The original camera negative of Film has been lost. For this 1080p, AVC-encoded Blu-ray from

Milestone Film & Video, a complete restoration was undertaken by documentary filmmaker Ross

Lipman, whose scholarly obsession with Beckett's only work of cinema resulted in the erudite

documentary, Notfilm. The

work of restoration was

performed by the UCLA Film & Television

Archive, using a fine-grain master positive supplemented by prints obtained from the British

Film Institute and producer Barney Rosset (who sadly passed away before seeing the finished

product). The result effectively reproduces cinematographer Boris Kaufman's careful delineation

between the camera's point of view and that of Buster Keaton's "O". The former is as sharp and

clear as the age and condition of the elements can support, revealing such details as the heavily

textured skin around the eye that opens Film, the rubble in the street outside "O's" room and the

room's cracked and peeling walls. As previously noted, "O's" point of view is deliberately

blurred, but the blurring is consistent in its densities. Blacks are solid, and carefully differentiated

shades of gray create a sense of depth where appropriate. The film's grain pattern is naturally

rendered. Milestone has mastered Film at an appropriately high average bitrate of 35 Mbps.

(Note that the video score at the top of this review is weighted toward accuracy, not prettiness.

The aesthetic behind Film does not make room for attractive vistas.)

Film Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Film's mono soundtrack has been restored from optical tracks and encoded in lossless PCM 2.0,

but it defies conventional description or scoring, because it's defined by the absence of sound.

There is no music of any kind, and the sole utterance—"Shh!"—is clearly reproduced.

Restoration supervisor Ross Lipman has added an additional subtle texture in an effort to re-create a theatrical experience. Since

early screenings

would

have been accompanied by the sound

of the theater's projector, Lipman has added a slight overlay of white noise, which is most

audible over the opening restoration credits, after which it fades. It's a winking nod to the analog

era in which Film was created.

How does one score a track like Film's? For sheer accuracy, it deserves top marks, but given how

review scores are typically interpreted, a high rating might suggest to readers a soundtrack

entirely different from the dead silence in which Film plays. The score on this review represents a

compromise, but the reality is that Lipman and his technical partners have done an exemplary

job.

Film Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

- The Dog and Cat Takes (1080p; 1.33:1; 8:15): These are outtakes from one of Film's comic routines. According to actor James Karen, the sequence was contributed by Keaton, who overcame the initial objections of Beckett and Schneider when they saw how well the gag played.

- Waiting for Godot (480i; 1.33:1; 1:44:21): This 1961 production of Beckett's best-

known

play was directed by Alan Schneider for a public television series called Play of the Week.

Burgess Meredith and Zero Mostel star as the hapless but energetic tramps condemned to

an apparently endless vigil in a blighted landscape. The videotape source has been

restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, and if you want to see just how much

it has been improved, compare the excerpts included in the documentary Notfilm.

Recurrent horizontal streaks remain, along with a few gaps and frame jumps, and the

sides of the frame are uneven, but the overall clarity is remarkable for a standard

definition source from over half a century ago. The soundtrack has been thoroughly

cleaned of static and hiss. The production is introduced by Barney Rosset, president of

Grove Press and producer of Film.

Having seen several excellent productions of Godot, I confess that I find Schneider's version somewhat wanting. Its chief weakness is its presentation of the imperious traveler, Pozzo, who is played by Broadway regular Kurt Kasznar at high volume but with a scattered focus. After experiencing memorable Pozzos from F. Murray Abraham, Christopher Lloyd and John Goodman, I've come to appreciate what a crucial and multifaceted role the character plays in creating Godot's world. But Mostel and Meredith are well-matched and ably capture the play's peculiar mix of vaudeville comedy and existential dread.

Film Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

Film may not be good—certainly no one involved was satisfied with it—but its historical

importance is undeniable, and it remains a fascinating artifact of a failed experiment. The rating

system used for film reviews simply doesn't apply to a work like Film, and the score that I have

assigned it is purely arbitrary. The work belongs to a realm of cinematic experiments so far

outside the norm that even the arthouse crowd will likely find it inscrutable, as did most film

enthusiasts of its era. But Film has something to say, even if it doesn't say it well—and there's

nothing like it. For those who want to see what it's all about, Lipman and Milestone have

provided a superb presentation. Be sure to follow up a viewing of this enigmatic curiosity with

Lipman's illuminating documentary.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

(Still not reliable for this title)

Birds of Passage

Pájaros de verano

2018

Aquarius

2016

Capital

Le capital

2012

Zama

2017

Goodbye to Language 3D

Adieu au langage

2014

Christ Stopped at Eboli

Cristo si č fermato a Eboli / Full-Length Version

1979

Memories of Underdevelopment

Memorias del subdesarrollo

1968

The Fire Within

Le feu follet

1963

Out 1

Out 1, noli me tangere

1971

Phoenix

2014

Stray Dogs

郊游 / Jiao you

2013

Through the Olive Trees

زیر درختان زیتون / Zire darakhatan zeyton

1994

Alambrista!

ˇAlambrista! / The Illegal

1977

Horse Money

Cavalo Dinheiro

2014

Beanpole

Дылда / Dylda

2019

Borom Sarret

included on "Black Girl" release

1963

Saute ma ville

1968

A Touch of Sin

天注定 / Tian zhu ding

2013

Pieta

피에타

2012

The Sicilian Clan

Le Clan des Siciliens

1969