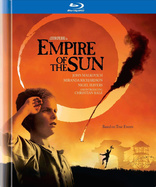

Empire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie

HomeEmpire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie

25th Anniversary EditionWarner Bros. | 1987 | 153 min | Rated PG | Nov 13, 2012

Movie rating

7.8 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 4.5 | |

| Reviewer | 4.0 | |

| Overall | 4.3 |

Overview

Empire of the Sun (1987)

A young English boy struggles to survive under Japanese occupation during World War II.

Starring: Christian Bale, John Malkovich, Miranda Richardson, Nigel Havers, Joe PantolianoDirector: Steven Spielberg

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Period | Uncertain |

| War | Uncertain |

| Biography | Uncertain |

| Melodrama | Uncertain |

| Epic | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1

French: Dolby Digital 2.0

Spanish: Dolby Digital 2.0

Portuguese: Dolby Digital Mono

German: Dolby Digital 2.0

Italian: Dolby Digital 2.0

Subtitles

English SDH, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese, German SDH, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Italian SDH, Mandarin (Simplified), Norwegian, Swedish

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Two-disc set (1 BD, 1 DVD)

Playback

Region free

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 4.5 | |

| Video | 4.5 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 3.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Empire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie Review

Spielberg's underrated classic boasts an excellent AV presentation...

Reviewed by Kenneth Brown November 17, 2012It isn't often that I step aside and give the floor to one of our readers. It's not that I believe that our membership's opinions are somehow inferior to mine. Far from it. One of my favorite pasttimes is scouring the forum and perusing user reviews for analyses and discussions about films I've either adored or perhaps too callously dismissed. Every once in a while, though, I come across a user review or in-depth forum analysis that so changes the way I view, understand and appreciate a film that I want nothing more than to showcase it. Enter our own Ernest Rister's "Empire of the Sun: Spielberg's Overlooked, Misunderstood Masterwork." Originally published in 1999, Rister's article is a fascinating, dare I say essential read, and a must for anyone who's intimately or even casually familiar with director Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun. Just one word of caution: newcomers to Empire should skip down to the video, audio and supplemental portions of my Blu-ray review, as Rister's film analysis is loaded with spoilers. Otherwise, the floor is his...

"In the short documentary The China Odyssey, Steven Spielberg talks about his take on author J.G. Ballard's semi-autobiographical novel, Empire of the Sun. Ballard's book details the author's own true-life experiences as a British child of privilege separated from his parents by the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in 1941, and one of Spielberg's boldest opinions of the work was that half of the book was a lie -- half of it true in the broad strokes, certainly, but it was Spielberg's belief that the details and vignettes were completely warped by Ballard's childhood perception.

This is crucial to understanding Spielberg's work on the film, which has long been dismissed or completely, fundamentally misread. Not a single shot can be trusted.

-

Jamie: I was dreaming about God.

Mary: What did he say?

Jamie: Nothing. He was playing tennis. Perhaps that's where God is all the time -- [in our dreams] -- and that's why you can't see Him when you're awake, do you think?

Mary: I don't know. I don't know about God.

Jamie: Perhaps He's our dream... and we're His.

Consider the scene referenced in italics above. Spielberg concludes this passage with a shot of Jamie in bed while his mother and father look on fondly. Spielberg's editor Michael Kahn then does something strange - he performs a quick dissolve of this same shot onto itself, which at first glance appears to be a gaffe. It isn't a gaffe. It's intentional. Spielberg wants you to remember this shot for an important reason.

Only later -- and only if you remember that odd dissolve -- do you see the payoff. Jamie becomes separated from his parents and spends the remainder of his childhood in a Japanese internment camp. He's spent years idealizing his parents to the point where he finally admits -- in a scene of tremendous power -- he can't remember what they look like any more. Subtly illustrating this point, hanging next to Jim's makeshift prison bed is a Norman Rockwell painting torn out of the pages of "Life" Magazine. The painting is of a mother and father looking fondly at a child in bed.

It is the exact same image from earlier in the film.

The implication here is that the earlier scene never happened, or at the very least didn't happen in the way Spielberg presented it to you -- the reality of the moment has been skewed by Jamie's fading memories. Either way, Spielberg's camera lied to you, and in 1987, it seemed like there wasn't a film critic in America who noticed.

Spielberg's camera is a font of dishonesty in Empire of the Sun, a blazingly original, criminally ignored film. Nothing in the frame can be trusted. Consider the first appearance of John Malkovich as the stranded maritime con man, Basie. When we first meet Basie, he is one cool customer; strongly back-lit, his face obscured by dark sunglasses and a G.I. cap. This is all fine and good, except Basie's appearance has already been foretold by the cover of the "Wings" comic book Jamie reads in the first moments of the film. The cover of the comic details a back-lit G.I., wearing dark sunglasses and a wide-brimmed cap. When the camera sees Basie, we see him as Jamie remembers him -- and Spielberg even cuts to the comic book to call your attention to the association.

In the closing moments of the film, Jim confronts Basie, and finds him a thin, shell of a man with bad skin, still pursuing his dream of being the pirate "lord of the Yangtzee." Is his physical condition simply the result of malnutrition? Unlikely, since at this moment Basie is in seemingly ample supply of Hershey's Chocolate bars. No, this is the real Basie. Not the idealized Basie, but the real Basie. Jim's days of hero-worship are over.

The truth is that Steven Spielberg made a film that toyed with reality as much as Rashômon. But because in 1987 he was critically regarded as a sort of live-action Walt Disney, a commercial filmmaker who distilled complexity down into family-friendly mass-market product, Spielberg's work in Empire was taken at face value, and the film was dismissed as a pointless failure.

Empire of the Sun would seem to be sitting up and begging for analysis, as it is so loaded with moments of fantasy and reverie in the midst of suffering. The film is all about the human need for escapism and denial in the face of a harsh reality, but it was received as a Shanghai version of An American Tail by way of a David Lean imitator suffering from Peter Pan syndrome. This was incorrect. Wildly incorrect. Many critics, in fact, directly faulted Spielberg for the unreality of Empire of the Sun and they took him to task for it. (Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were particularly harsh.) They missed the point. Spielberg literally lifts the subconscious interpretation of events by a 12 year-old boy and prints those memories onto film. The prison camp - which was criticized for being a fantasy construct and not a real environ - exists as the child remembers it. Since children can have quite a fine time with a cardboard box, you can imagine how much fun a boy who loves planes had living next to an airfield. Spielberg puts that interpretation on film.

It is said that there are two types of media -- lean-forward media and lean-back media. Lean-forward media asks you to participate, to do your own work, to sort things out. Lean-back media does all the work for you, the film acts upon you, as opposed to you injecting yourself into the film. Raiders of the Lost Ark is a lean-back movie. E.T. is a lean-back movie. Jaws is a lean-back movie. Even The Color Purple is a lean-back film.

Empire of the Sun is a lean-forward film, but because Spielberg had created so many masterful films in the classic Alfred Hitchcock, Frank Capra, John Ford, and Walt Disney mold, this is what people expected from him. Empire of the Sun was something completely new from Steven Spielberg - a film that worked on multiple levels of reality, with one informing the other. Audiences and critics did not know what to make of it.

Spielberg became a victim of his own success. Having proven himself a master of fantasy and special f/x, audiences and critics took his visuals - some of them subtle, some of them wildly abstracted - at face value. The film is jammed full of impossible moments that clearly are not happening, including a toy glider that stays impossibly aloft, the aforementioned scene involving the family, a trio of pilots who salute the young boy in a hail of welding sparks, a pilot of a P-51 who waves to Jim, a refrigerator that bursts open revealing - instead of food - glitter and toys... there's a gesture that Jim sees his father perform, rubbing his finger across his upper lip. Later, Jim will have a new father figure, Dr. Rawlins, who will repeat the same gesture. Film critic Patrick Taggart actually asked what the point of this gesture was. Years later, I'm happy to tell him the gesture is the result of Jim's fading recollection of his parents. He remembers his father making the gesture, and as Dr. Rawlins becomes his "new" father, Jim begins superimposing attributes onto him, including his father's own mannerisms. It could actually be the reverse - with the earlier shots of the father actually warped by the later memories of the prison camp. Again, nothing can be trusted.

Spielberg reveals this inner life to us in an enormously subtle way. The standard practice for "interior point of view" scenes is to clue the audience in by the use of hazy wipes and dissolves, or cross cutting between "interior pov" and "actual pov." Spielberg discarded these devices completely, trusting in the intelligence of his audience. He does use slow-motion and the occasional absurd image to try and drive his message home, but in Empire of the Sun, he's more apt to lead you to the truth from the edges. One quick throw-away spotlights the British POWs reading from "A Midsummer Nights Dream" as Jim races by, a little clue to the movie's intentions that Spielberg slips by you, almost subliminally.

The film is about escapism, how it can kill. Time and time again, Spielberg and his screenwriter Tom Stoppard serve up an entire cast of characters who choose to ignore the reality of the world around them and end up emaciated shells of their former selves or worse. The film's message seems to be that in the face of such a serious reality, denial and escapism are deadly, and the world must be dealt with on its own terms. Jim's Great Dream -- other than flying -- is to reunite with his parents, and he carries all of his childhood memorabilia in a small suitcase. Jim must forsake this fantasy and grapple with reality -- this suitcase that contains his dreams will later be seen in a closing coda that mirrors the opening shot of the movie -- the dead floating in the Shanghai Harbor.

Because of his pre-occupation with exploring this theme, Empire of the Sun is unique in the Spielberg canon in that it is a film less concerned with plot than it is with examining an idea -- the value and necessity for denial and escapism -- and all the ways the human animal lies to itself. The unfortunate result is a film that winds down emotionally by the end of its second hour, and it has been called a somewhat distant film. Movies are things we go to for many reasons, but, as Roger Ebert says, we primarily go because we want to feel something. Works like Empire of the Sun border on functioning like a parlor-game -- they're a great work-out for the left-side of your soul and a litmus test for how you view film, but they're also a bit emotionally cold. This oft-repeated criticism of Empire of the Sun -- that it fails to engage in its latter scenes -- isn't something so easily dismissed away. Lawrence of Arabia sported a hole in the center of its drama in the shape of a man who was a total enigma. Empire of the Sun -- which David Lean himself was attached to at one point -- also has a protagonist at its center who is emotionally distant, keeping the viewer at arm's reach. The difference is that, in Lawrence, you had a man of fathomless interest and contradictions at its fore, and in Empire of the Sun, you had a spoiled child.

To me, Empire of the Sun represents the death of the Spielberg I grew up with, just as much as it tells the tale of a child who must shuck off the best parts of childhood in order to survive. Its my personal belief that the failure of this film was a giant blow to the man, whose career went into a brief artistic tailspin even as it was generating ever-higher box office returns. Looking back, I can't help but sense that Spielberg tried to grow as an artist, and was rejected and dismissed, and so, returning to his bread and butter, felt bored and and disinterested. Spielberg's public quotes around this time are the most self-loathing of his life, referring to works like Hook as "hamburgers" and himself as little more than a McDonald's fry chief.

Spielberg would be reborn in 1993 with Schindler's List, and he has since proven beyond little doubt that he is at the top of his game when he tackles new and challenging material. Empire is a film from the "new and challenging" category, and the great thing about home video is films can have a second chance, and it is never too late to rediscover a buried classic. Empire of the Sun deserves your attention, but what's more, I think Spielberg's work in the film deserves your open mind and your further contemplation."

-

Empire of the Sun: Spielberg's Overlooked, Misunderstood Masterwork

by Blu-ray.com member Ernest Rister, republished here with his permission

Empire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

After being subjected to a number of delays earlier this year, I wasn't sure what to expect from Empire of the Sun's Blu-ray debut. I'm pleased to report, though, that I was completely taken with Warner Bros.' faithful, utterly filmic 1080p/AVC-encoded video transfer; a striking, near-perfect catalog presentation with nothing in the way of distractions. If any complaint can be leveled against the image it's that black levels are sometimes muted, with dusty charcoal tones dominating the darkness. But boosting contrast to compensate would have hampered Allen Daviau's cinematography and the dreamlike atmosphere Spielberg often evokes. By staying true to the source, crush isn't a factor, delineation is revealing and shadows still exhibit satisfying depth and darkness. Colors aren't overbearing either. Daviau's palette is subdued but natural, skintones are beautifully saturated and exceptionally lifelike, primaries pop when called upon, and contrast is consistent throughout. Detail is also excellent, with crisp, clean edges, nicely resolved fine textures and a faint veneer of pleasant grain. Significant artifacting, ringing, banding, aliasing and errant noise aren't at play, and there aren't any troubling anomalies of note. In short, Empire of the Sun stands as one of Warner's best catalog presentations of the year.

Empire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Warner's DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track is quite good too. It just lacks the power and punch of a top-tier war-movie mix. Dialogue is clear, intelligible and terrificly prioritized, and silence are filled with distinct breathing, the flickering of distant fires, the crunch and shuffle of footsteps, the hum of circling planes, the rustling of grass, and a host of other light ambient effects and nuanced atmospherics. Ample rear speaker activity makes it all a reasonably immersive experience, even if hushed scenes occasionally engage every channel a bit more assertively than chaotic sequences. LFE output, though, is more than serviceable but a tad thin at times, and doesn't grant each and every engine roar and explosion the raw, earthy oomph they appear to warrant. (Some sound great, mind you.) There are also a few scenes -- Jamie's visit with Basie in the hospital for one -- that exhibit an obvious noise floor. All that being said, there's nothing here that suggests the track is anything less than respectful of the film's original sound design. John Williams' score is given full reign of the soundfield (the lovely Welsh lullaby, "Suo Gân," is more stirring than its ever been), dynamics are commendable, directionality is decidedly decent and pans are smooth. In the end, Empire of the Sun's AV presentation delivers, and then some.

Empire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

- The China Odyssey (Disc 1, SD, 49 minutes): Narrated by actor Martin Sheen, this behind-the-scenes documentary delves into the history of the Japanese occupation of Shanghai, life in the International Settlement, the film's adaptation and production, Spielberg's Chinese location shoot, his wrangling of hundreds of extras, and his work with his actors, young and old. Between the candid fly-on-the-wall footage included, the scenes in which Spielberg helps shape a young Christian Bale's performance, and interviews with several people who survived the Shanghai occupation (from author J. G. Ballard to elderly locals) makes this a must-see documentary for anyone who enjoys Spielberg's Empire of the Sun.

- Warner at War (Disc 2, SD, 47 minutes): Steven Spielberg explores Warner Bros.' efforts to say what other studio heads and politicians of the era weren't quite ready to say, taking the offensive with anti-Nazi films and shorts -- movies like Confessions of a Nazi Spy in 1939 -- the Warner brothers used to prepare the American public for war, fend off accusations and defy government attempts to suppress information (Sergeant York) and, eventually, to offer audiences a source of news, recruitment, calculated propaganda, war bond sales and morale throughout World War II.

- Theatrical Trailer (Disc 1, SD, 2 minutes)

Empire of the Sun Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

I already felt a deep affection for Empire of the Sun, having first watched it when I was just a boy and then revisiting it time and time again over the years. This time, though, I was armed with a new perspective -- Rister's Empire of the Sun: Spielberg's Overlooked, Misunderstood Masterwork" -- and it expanded my understanding and appreciation of the film almost exponentially. It was like watching it for the first time, my eyes open to everything Spielberg and Stoppard had accomplished before being tragically dismissed by the critical masses. This is one that deserves reconsideration and reevaluation, and I look forward to watching it yet again the moment this review posts. Fortunately, Warner's Blu-ray release rises above its delays and impresses with an excellent AV presentation. New special features would have certainly been welcome (as it stands the 2-disc 25th Anniversary Edition DigiBook includes just two SD documentaries), but it doesn't matter much in the grand scheme of things. Empire of the Sun isn't actually the film most people have seen. The real Empire is richer, more haunting and more moving than even I once gave it credit for being. Rister said it best: "it's never too late to rediscover a buried classic."

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

The Pianist

2002

Schindler's List 4K

25th Anniversary Edition

1993

Rescue Dawn

2006

The Railway Man

2013

Patton

1970

The Great Escape 4K

1963

The English Patient

1996

The Bridge on the River Kwai

1957

The Last Emperor 4K

Theatrical (4K/BD) and Television (BD) Versions

1987

The Way Back

2010

The Children of Huang Shi

Limited Edition

2008

Mongol: The Rise of Genghis Khan

2007

The Deer Hunter 4K

Collector's Edition

1978

Papillon

1973

Seven Years in Tibet

1997

The Counterfeiters

Die Fälscher

2007

The Sand Pebbles

1966

Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence

1983

Lawrence of Arabia 4K

60th Anniversary Limited Edition

1962

The Flowers of War

金陵十三钗 / 金陵十三釵 / Jīnlíng Shísān Chāi

2011