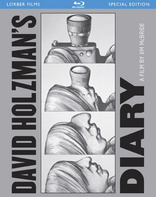

David Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie

HomeDavid Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie

Special EditionKino Lorber | 1967 | 74 min | Not rated | Aug 16, 2011

Movie rating

7.1 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 4.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Overview

David Holzman's Diary (1967)

This fake documentary which appears quite real on the surface is about a young man making a movie about his everyday life and discovering something important about himself and his reality. This film is not a real documentary or is it?

Starring: L.M. Kit CarsonDirector: Jim McBride (I)

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Comedy | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 1.34:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.37:1

Audio

English: LPCM 2.0

Subtitles

None

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Playback

Region A (B, C untested)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 4.5 | |

| Video | 4.0 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 3.5 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

David Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie Review

Cinéma vérité, sans vérité.

Reviewed by Casey Broadwater August 2, 2011Director Jim McBride has a varied filmography that gets stranger the further you trace it back. In the early 2000s and 1990s he worked exclusively-- and only sporadically--in television, helming episodes of Six Feet Under, Fallen Angels, and The Wonder Years. In the ‘80s, he made a Jerry Lee-Lewis biopic, Great Balls of Fire!, along with a much-maligned, but rather cool remake of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, and in 1971 he directed the X-rated Glen and Randa, a lightly softcore post-apocalyptic sex-and-survival movie. His first film, however, 1967’s David Holzman’s Diary, is his most important and influential, a pseudo-documentary that satirizes the self-reflective style of autobiographical cinema only recently pioneered by Jonas Mekas, Maya Deren, and other avant-garde filmmakers of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. It’s one of the first examples of what’s commonly called the “mockumentary,” but it’s also something quite more than that--a time capsule of Vietnam-era New York, a meditation on artistic narcissism, and an expression of McBride’s ideas on film theory. Like Orson Welles’ F for Fake and Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-up, David Holzman’s Diary blurs the line between art and reality, illusion and truth, occupying that muddled, indistinct place in between.

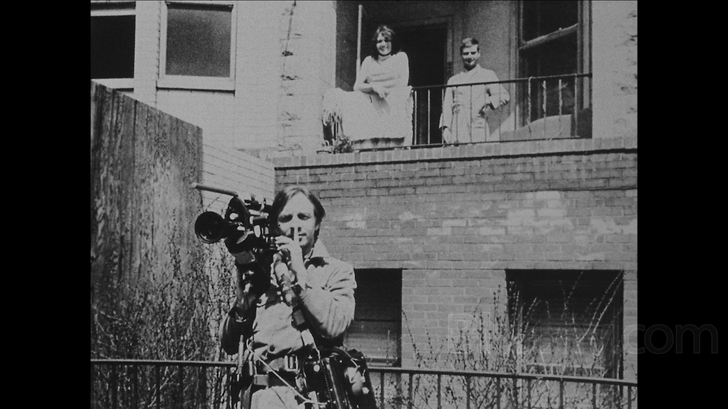

Man with a Movie Camera

If cinéma vérité superstar Dziga Vertov hadn’t already made a film called Man with a Movie Camera in 1929, it would’ve been the perfect title for David Holzman’s Diary, which is both a critique of and an homage to the style of filmmaking Vertov helped create. More explicitly, Diary is also, on one level, a film about the connection between the director and the main tool of his trade--the camera. As the fake documentary opens, made-up filmmaker David Holzman--played by a mop-haired L.M. Kit Carson--is filming himself in a mirrored window while people come and go on a New York street behind him. It’s July 14th, 1967, and Vietnam is in full swing. Holzman, newly unemployed and imminently eligible for the draft, has decided to “do something that’s been on [his] mind for a long time,” to document every facet of his life with his trusty 16mm Arriflex and a portable reel-to-reel tape recorder.

In an early scene he sits across from the camera and details his motivations, citing “noted French wit” Jean-Luc Godard, who said that “film is truth 24 times a second.” Holzman believes that “if I put it all down on film...I should get the meaning, I should understand it.” Of course, Godard also said that “cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world,” and Holzman only comes to understand this after his obsession with self-documentation essentially ruins his relationship with his girlfriend, Penny (Eileen Dietz), a model and “it” girl who quickly becomes fed up with having a camera shoved in her face.

At the core of David Holzman’s Diary is this contradiction, that film can simultaneously lie and tell the truth. It’s the cinematic equivalent of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principal--reality might still be “real” when documented, but the outcomes are changed by the very act of observation. In the 1960s, this caused a methodological split between North American “direct cinema” documentarians like D.A. Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers-- who took a discrete, “fly on the wall” approach to filming their subjects--and their European, cinéma vérité counterparts, like Jean Rouch, who acknowledged the camera’s role and even used it to provoke certain responses. In his film Chronicle of a Summer, Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin discuss whether or not it’s possible for a subject to be authentic in front of a camera, and McBride frames this same debate in Diary with a scene in which Penny’s manager--who wants to get into her pants--delivers a lengthy monologue about how the camera’s presence makes you “very self-conscious about everything you do.” This doesn’t stop David, who continues his quest for truth, aggravating Penny in the process. The final straw is when he films her sleeping naked in bed--he says the mise-en-scène reminds him of a “diorama at the Smithsonian”--only to face her ire when she wakes up to the camera’s leering gaze.

We might as well turn here to another quote from Godard: “The cinema is an x-ray machine in which one photographs one’s own disease.” David’s particular ailment is extreme narcissism coupled with Peeping Tom-esque voyeuristic tendencies. As the film progresses through the span of a week in David’s life, we see him as increasingly obsessive and maybe even a little unhinged. From afar, he compulsively films the comings and goings of a woman he calls “Sandra,” who lives across the street and has no idea David’s camera is pointed into her living room as night. In a genuinely unsettling sequence, he follows another woman off a subway car and trails her as she walks ever faster through the street, aware that he’s behind her.

At the outset, though, we’re somewhat sympathetic with David--even if he’s never exactly likable--simply because he’s so determined and strangely charismatic, taking his 16mm rig with him everywhere he goes. When he gets a new fisheye lens for his Arriflex, he joyfully runs out in the street to test it, holding the camera above his head, blithely unconcerned that people must think he looks like a lunatic. Throughout, McBride-as-Holzman edits in footage of summertime life in New York, and this non-staged material--old people lining park benches, toughs hanging around the block, police walking the beat--not only stands today as a reminder of how the city and its citizens used to look, but it also helps sell the otherwise fictional film’s illusion of reality. One of the highlights of the movie is a comically unscripted scene where David interviews a real-life post-op male-to-female transexual nymphomaniac who basically propositions him by the end of their literally traffic-halting conversation. It’s too strange to not be true.

David Holzman’s Diary satirizes the “confession booth” trope of reality TV shows before there ever was such a thing. It foreshadows the user- generated content of YouTube and prefigures the navel-gazing self-absorption of social media. McBride was reacting to a very specific type of 1960s filmmaking, but Diary holds up remarkably well today for the way that it seems to anticipate and pre-mock the new forms that “cinéma vérité” would take in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Ultimately, it’s a film that’s both of its time and ahead of its time, part truth, part lie, and wholly worth revisiting.

David Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Shot on an $2,500 budget--and intended to look like a film shot on next to nothing--David Holzman's Diary has nonetheless been beautifully restored by the Pacific Film Archive, the University of California, and the Berkeley Art Museum. The intent here was clearly to provide as faithful of a restoration as possible, to simply clean the dirt and debris from the 16mm footage and balance the black and white gradation, but leave it otherwise untouched by digital sharpening, noise reduction, or other attempts at artificially boosting the image. The 1080p/AVC-encoded transfer looks wonderful, with a natural grain structure and an image that's as resolved as you can expect from the source material. Yes, there's not nearly as much fine detail as you'd find in a 35mm film, or even in most 16mm productions, but I can't imagine the film looking any more crisp without the use of edge enhancement, which would seriously affect the integrity of the picture. What's important here is that black levels are deep, whites never look overblown- -although they could perhaps be a hair brighter--and there are no compression problems or encode issues to report.

David Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

The film's uncompressed Linear PCM 2.0 mono track is also another case of "this is probably as good as it ever can or will be." Diary's reel-to-reel recordings are intentionally lo-fi, and any attempt to excessively remove hisses, clicks, thumps, and muffling would remove much of the movie's low- budget charm and believability. Make no mistake, this track will grate on the ears of most audiophiles, but it is what it is and it's presented truthfully. Audio clips from Vietnam newsreels, New York city street clamor, and lightly muffled dialogue all compete for space in Diary, and the result is often a cacophony of sound, underscored by quiet but definitely present tape hiss. Vocals are occasionally buried in noise, but if you pay attention you can generally make out everything that's being said. Unfortunately, the disc has no subtitle options whatsoever.

David Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

Kino-Lorber has generously included three bonus documentaries with this release, two from the years immediately after David Holzman's Diary, and one made by McBride in 2008.

- My Girlfriend's Wedding (1080p, 63 min.): In 1969, McBride followed up Diary with a film that, in many ways, is its opposite. Where Diary is a faux-documentary that seems real, My Girlfriend's Wedding is a genuinely real account that's almost too hard to believe. Most of the film consists of long interviews with McBride's English girlfriend, Clarissa Ainley, who describes her troubled past, her thoughts on the counterculture "revolution," and her ploy to marry another man in order to stay in America. (I was confused at first as to why she couldn't simply marry McBride, but after some internet sleuthing, I discovered he was still married to, but separated from, his wife at the time.)

- Pictures from Life's Other Side (1080p, 45 min.): A loose sequel to Wedding, 1971's Pictures charts McBride and a pregnant Ainley's cross-country journey to Los Angeles, where they hope to make a new home. It's a road movie with frank sexuality, interesting family dynamics, and plenty of Americana scenery.

- My Son's Wedding to My Sister-in-law (1080i, 9 min.): In 2008, McBride made this short film about the complicated web that is his extended family.

David Holzman's Diary Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

David Holzman's Diary is definitely an artifact of 1960s underground cinema, but it's strikingly relevant today in light of the ways in which the underlying concepts of cinéma vérité and "personal" filmmaking have morphed into the constant self-reflection of reality television and social media. Fans of low-budget independent filmmaking should check out Kino's Blu-ray release, which looks wonderful and contains director Jim McBride's following documentaries, My Girlfriend's Wedding and Pictures from Life's Other Side, two deeply personal--and real--home movie experiments, both of which are worth your time. Recommended!

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Greetings

1968

The President's Analyst

Special Edition

1967

Hi, Mom!

1970

Chained for Life

2018

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice

Limited Edition to 3000

1969

Daisies

Sedmikrásky

1966

Il Sorpasso

The Easy Life

1962

The Square

2017

A King in New York

1957

Wiener-Dog

2016

The Pawnbroker

1964

Something Wild

1961

WR: Mysteries of the Organism

W.R. - Misterije organizma

1971

M. Butterfly

1993

The Landlord

1970

Bananas

1971

Putney Swope

1969

Greener Grass

2019

Zama

2017

Aquarius

2016