Contempt Blu-ray Movie

HomeContempt Blu-ray Movie

Le mépris / StudioCanal CollectionLionsgate Films | 1963 | 103 min | Not rated | Feb 16, 2010

Movie rating

7.4 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 4.5 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

Overview

Contempt (1963)

A screenwriter finds his marriage falling apart as he attempts to start a film version of the "The Odyssey."

Starring: Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, Fritz Lang, Giorgia MollDirector: Jean-Luc Godard

| Drama | Uncertain |

| Foreign | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080p

Aspect ratio: 2.33:1

Original aspect ratio: 2.35:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio Mono

French: DTS-HD Master Audio Mono

German: DTS-HD Master Audio Mono

Spanish: DTS-HD Master Audio Mono

Subtitles

English, German, Japanese, Spanish, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Single disc (1 BD)

Packaging

Slipcover in original pressing

Playback

Region A, B (locked)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 5.0 | |

| Video | 3.5 | |

| Audio | 4.0 | |

| Extras | 4.5 | |

| Overall | 4.5 |

Contempt Blu-ray Movie Review

“Cinema shows us a world that fits our desires. Contempt is the story of that world.”

Reviewed by Casey Broadwater February 16, 2010New Wave auteur Jean Luc-Godard once famously declared that cinema is “truth twenty four times per second.” Then again, he also said that cinema is “the most beautiful fraud in the world.” So, which is it? Can it be both? Are the two assertions necessarily mutually exclusive? It seems that for Godard—perhaps the ultimate cineaste—the most important thing is that cinema simply is. The synthesis of both of his statements is that, like all art, cinema is essentially a grand illusion staged around a kernel of truth. Philosophically, it goes back to the differentiation between the real and the Platonic ideal—the disconnect between objects and ideas—and Godard’s films frequently engage in a kind of cinematic dialectic where opposing forces are indirectly represented by the characters or their conflicts. This is never more apparent than in Le mépris—the director’s sixth feature—which is not only structured around thematic oppositions, but is itself a contradiction: an art film posing as a big-budget commercial movie, or vice versa. Or, perhaps, both.

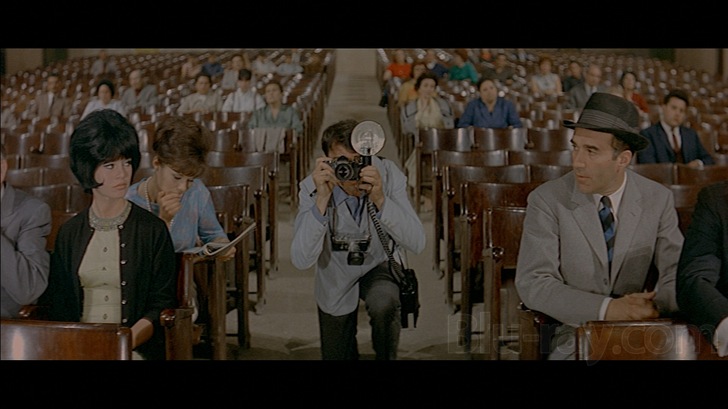

CinemaScope: Ideal for snakes, funerals, and showing both sides of the aisle.

Godard’s first feature, Breathless, is aptly titled. This and his other early films, like Le petit soldat and Vivre sa vie, are intoxicating displays of the director’s manic cinematic energy, marked by a rule-breaking, low-budget, borderline improvisatory filmmaking style that would come to define the French New Wave. With Le mépris, a co-venture between Italian producer Carlo Ponti and American schlockmeister Joseph E. Levine, Godard was handed his biggest budget yet. Not unexpectedly, this was both a blessing and a curse, and I’m sure that if he had made the film today, Godard—who was always enamored with American pop culture—would be quick to quote The Notorious B.I.G.’s ageless maxim, “mo’ money, mo’ problems.” In Godard’s case, more money meant more bending to the will of his producers. Ponti and Levine picked original tabloid superstar and international sex symbol Brigitte Bardot for Le mépris’ female lead, hoping to bank on her nude body, but they were distressed by Godard’s first cut, which was free of any gratuitous erotic thrills. Tasked by his financiers with bumping up the film’s flesh quotient, Godard did what any self-respecting auteur would—he did it his way, inserting nudity into the plot organically, with a chaste air that seems more tragic than titillating. In the first scene after the reflexive credit sequence—which I’ll get to in a second—we see Bardot, lying naked on her stomach, in bed with her co-star Michel Piccoli. They play a young married couple; she’s Camille, a 28-year old typist, and he’s Paul, a writer. In this prologue—which is alternately cast with red, yellow, and blue color filters—Camille asks Paul if he likes her feet, her ankles, her knees, her thighs, etc., all the way up to her face. Paul responds that he loves her “totally…tenderly…tragically,” setting up one of the narrative’s central concerns: the dissolution of their marriage.

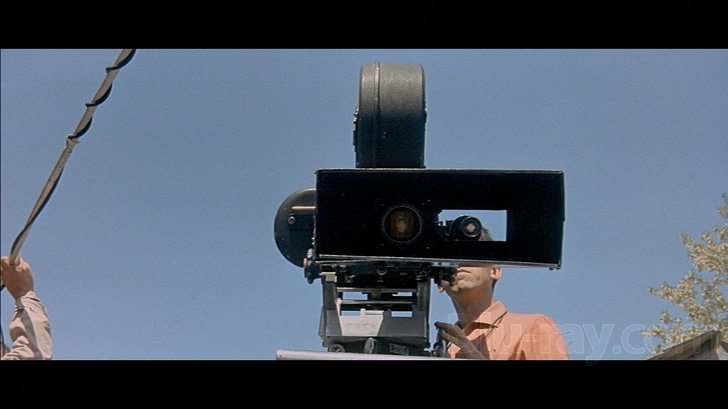

While the end of the couple’s love is the film’s emotional core, Le mépris’ intellectual center is preoccupied with the end of cinema itself, or at least the particular brand of Hollywood moviemaking—the “days of Chaplin and Griffith,” says one character—that died out with the advent of television. 1963 was something of a banner year for films about filmmaking—Fellini had just released 8 1/2—and Le mépris announces its meta-cinema intentions with a clever credit sequence that shows a camera on a dolly track coming ever closer, and finally panning and angling down so that the lens is pointing straight at us. Or, rather, pointing directly at the capturing eye of Godard’s camera. But the mirroring doesn’t stop there. In a bit of irony so precise that it almost feels staged—like a brilliant publicity stunt—Godard’s own troubles with his producers are reflected in Le mépris’ storyline, which features one of Godard’s cinematic heroes, Fritz Lang, playing himself, trying to shoot an adaptation of Homer’s The Odyssey. Lang is representative of Hollywood’s old guard—Howard Hawks, Hitchcock, and of course, himself—and his vision for the film is at odds with that of Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance), a slimy and arrogant American producer who wants to supplement the story with nudity and take a modern, psychoanalytical approach to the character of Penelope, questioning her fidelity to her husband Ulysses. Paul agrees to do rewrites on the script, but the project puts his marriage on the rocks. Suddenly—within the span of an afternoon—Camille feels a deep-seated contempt towards him. Is it because she thinks he’s selling out? Or is because Paul fails to defend her when Prokosch makes a pass at her?

As is often the case in real life, Camille’s reasons are myriad and, ultimately, undisclosed. Even the 30-minute argument that takes place in the couple’s flat reveals little about her motivations, though this nearly real-time scene is absolutely entrancing as a portrait of a dissolving relationship. Naturally, it’s easy to see Paul as Godard himself, Camille as his wife Anna Karina— especially when Bardot dons a black wig, subverting her blond sexpot image—and Prokosch as producer Joseph Levine, but the film’s symbolism goes beyond the merely biographical. An alternate reading has Paul as Ulysses, Prokosch as arch-nemesis Poseidon, and Camille as faithful Penelope—though it’s perhaps a stretch to see Fritz Lang as Poseidon’s son, the cyclops Polyphemus, even though Lang does wear a monocle. Godard uses the film’s relatively straightforward narrative—indebted to Alberto Moravia’s novel A Ghost at Noon—as a base on which to pile layers of interconnected meaning. And if there’s one overriding reason why Le mépris is a withstands-the-test-of-time classic—besides the gorgeous cinematography of Italy’s Capri coastline, the convincing, multi-lingual performances, and the film’s faultless sense of style—it’s that each new viewing is like an archeological excavation that uncovers more cinematic treasures, and a deeper understanding of the film’s intent.

Ever the aesthete, the director uses primary colors as thematic touchstones—the blue of the ocean, Prokosch’s red sports car, Camille’s yellow towel—and he continually contrasts the old with the new. See the Greek sculpture next to a modernist couch in the apartment, or notice how Paul wears a dapper, contemporary hat as well as a bathrobe that looks like a toga. And, of course, Fritz Lang’s film-within-a-film version of The Odyssey—one of the oldest tales known to man—is told in bright, pop-art colors that wouldn’t look out of place in an Andy Warhol print. In the final scene, Lang is framing a shot of Ulysses looking out at Ithaca, his homeland, after years of wandering. As the cinematographer moves the camera in a slow tracking shot of the hero with his arms raised—followed by real cinematographer Raoul Coutard, filming the filming of a film—we see that there is no homeland, only an empty stretch of ocean as far as the eye can see. It’s as if Godard is saying you can never go back—not home, not in love, and not to the old methods of filmmaking—but that there’s always a new wave.

Contempt Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

Paul Javal: I like CinemaScope very much.

Fritz Lang: Oh, it wasn't meant for humans. Just for snakes…and funerals.

Le mépris arrives on Blu-ray in the U.S. with the same 1080p/AVC-encoded transfer that

Studio Canal prepared for the film's high definition debut in France, Germany, and the U.K. While

the film hasn't received a full restorative overall—unlike Criterion's spectacular recent release of

Godard's Pierrot le fou—Le mépris is still a thing of beauty on Blu-ray, marred

only a by a few inconsistencies and some source elements that are less than pristine. Presented

in its glorious 2.35:1 original CinemaScope aspect ratio—clearly, Godard didn't feel confined to

snakes and funerals—Le mépris looks beautiful in motion and proves to be a substantial

upgrade from Criterion's 2002 DVD release. The bump in overall clarity is definitely appreciable,

with close-ups displaying cleaner textures and longer shots carrying a tighter, more detailed

appearance. Before the opening credits, a disclaimer pops up that reads, "The original cut of this

film contains scenes that are missing from the English version. We now present these scenes

with their original soundtrack and English subtitles." From the looks of it, these scenes were

sourced from entirely different elements than the rest of the film, having a softer, flatter, almost-

duped look that makes them stand out oddly. That said, there are only a few of these scenes—all

quite short—and I appreciate having a more complete cut of the film.

Of course, color is of utmost importance in Le mépris, and this transfer handles the film's

plentiful primary tones with ease. Saturation is right on target, contrast is strong, and the color

balance in general looks more natural than in the Criterion DVD. There are, however, some minor

color fluctuations from time to time, along with

the occasional pulse of contrast wavering. None of this is distracting, though, and there were very

few instances when my eyes were pulled from the experience of watching the film to notice some

technical anomaly. I did spot some minor telecine wobble—when the image appears to subtly

shake from side to side—but edge enhancement is absent, the film's grain structure is intact, and

aside from a brief spurt of small brown stains at the 46:42 mark and a few scattered white

specks, the print is in fairly good condition. Likewise, there are no compression-related issues to

report. Could the film look better? Probably—with a more intensive image overhaul—but I'm

more than pleased with the transfer Studio Canal has put together. Le mépris and

Bardot have never looked better.

Contempt Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Studio Canal wisely decided against trying to expand the film's original monaural soundtrack into a 5.1 mix, and have loaded up this disc with four DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 tracks—in the original French, along with English, Spanish, and German dubs. Le mépris' multi-lingual dialogue is essential to the feel of the film, so if possible I'd recommend sticking with the original French mix, which preserves the English, German, and Italian that's also spoken by the characters. To put it simply, I have no real qualms about this track. Yes, to modern ears it can feel a bit brash at times— the weight is mostly on the mid-to-high end—but this is how the film has always sounded. Georges Delerue's aching score is powerful and detailed, though, and the dialogue is clean and nicely balanced. For those of you who aren't polyglots—myself included—the disc also includes English, German, Castellan, Spanish, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Finnish, Swedish and Japanese subtitles, which, when turned on, appear inside the image in easy-to-read white lettering.

Contempt Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

Introduction by Colin MacCabe (SD, 5:31)

Writer and producer Colin MacCabe gives a brief sketch of the film's production and explain how

Le mépris' large budget ties in to its relative conventionality compared to Godard's other

films.

Once Upon a Time There Was...Contempt (SD, 52:28)

Featuring fascinating interviews with the always frank Godard—who chain smokes cigars

throughout—Once Upon a Time is an enlightening history of Le mépris that

combines a documentary-style narrative with Godard's own thoughts about the film. This is

essential viewing for all Godard fans.

Contempt...Tenderly (SD, 31:31)

Though somewhat redundant considering the exhaustive nature of the previous documentary,

this making-of special features a few new insights by way of French writer Alain Bergala, who

discusses the often under-acknowledged influence of Alberto Moravia's novel on Godard's

film.

The Dinosaur and the Baby (SD, 1:00:57)

How often do you get to hear two titans of cinema chat about their work for an hour? Here, Fritz

Lang and Jean-Luc Godard—the dinosaur and the baby, respectively—discuss everything from

censorship and filmmaking philosophies to practical scene blocking techniques. Their eight-part

conversion is intercut with scenes from M and Le mépris. The highlight of the

bonus features, in my opinion.

Conversation with Fritz Lang (SD, 14:27)

Made on the set of Le mépris, this brief, vintage EPK-style featurette shows Fritz Lang

discussing the role of a film's producer, amongst other things, but he seems slightly annoyed by

the interviewer's often-obvious questions. More notably, get to see an alternate take of the scene

where Prokosch throws a film reel like a discus.

Booklet

Taking a cue from Criterion's classy inserts, Le mépris includes a full color 18-page

booklet with an essay by Ginette Vincendeau.

Trailer (SD, 2:32)

BD-Live Functionality

Contempt Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

Le mépris is perhaps Godard's most conventional film, but within the commercial, big- budget construct he was forced to work within, he created a lasting piece of cinema that's as layered and intellectually stimulating as it is sensual. Sure, it's somewhat of a bummer that Criterion lost the rights to this and several other Studio Canal titles, but I'm just happy to see classic films being released on Blu-ray. And really, despite the lack of a true restorative visual overhaul, Studio Canal has done a fantastic job with this release, which looks and sounds great, and includes a truly excellent supply of supplementary materials. Highly recommended.

Other editions

Contempt: Other Editions

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

A Woman Is a Woman

Une femme est une femme

1961

Pierrot le fou

1965

Breathless

À bout de souffle

1960

Vivre sa vie

Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux / My Life to Live

1962

Red Desert

Il deserto rosso

1964

Belle de jour

1967

La Dolce Vita

1960

The 400 Blows

Les quatre cents coups

1959

A Married Woman

Une femme mariée: Suite de fragments d'un film tourné en 1964

1964

L' Avventura

1960

Alphaville 4K

Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution

1965

Last Year at Marienbad 4K

L'année dernière à Marienbad

1961

Cobra Verde

1987

Beau Travail

1999

The Seventh Seal 4K

Det sjunde inseglet

1957

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

1975

La Notte

1961

Léon Morin, Priest

Léon Morin, prêtre

1961

Port of Call

Hamnstad

1948

After the Rehearsal

Efter repetitionen

1984