Baseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie

HomeBaseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie

A film by Ken Burns and Lynn NovickPBS | 2010 | 241 min | Not rated | Oct 05, 2010

Movie rating

7.8 | / 10 |

Blu-ray rating

| Users | 0.0 | |

| Reviewer | 4.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Overview

Baseball: The Tenth Inning (2010)

1992 - 2009: As the tumultuous twentieth century is drawing to a close, and a new millennium begins, baseball continues to reflect the complicated country that created it. In an age of globalization and speculation, the players and the owners wage a cataclysmic battle over money and power; dazzlingly talented Latin and Asian stars transform the game; Cal Ripken becomes the game's new Iron Man; sluggers Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa and Barry Bonds do things that have never been done before; the Yankees build a dynasty while their arch rivals, the Red Sox, stage the greatest comeback in history. And in September of 2001, at a time when America seems most threatened, baseball offers the hope that things will one day return to normal. The national pastime is more popular, and more profitable, than ever, but suspicions and revelations about performance enhancing drugs keep surfacing, threatening the integrity of the game itself. Still, through it all, baseball endures, a game of infinite possibility and surpassing beauty.

Starring: Mark McGwire, Jose Canseco, Barry Bonds, Steve Bartman, Ichiro Suzuki (I)Director: Ken Burns

| Sport | Uncertain |

| Documentary | Uncertain |

| History | Uncertain |

Specifications

Video

Video codec: MPEG-4 AVC

Video resolution: 1080i

Aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.78:1

Audio

English: Dolby TrueHD 5.1

Spanish: Dolby Digital 2.0

Subtitles

English SDH

Discs

50GB Blu-ray Disc

Two-disc set (2 BDs)

Playback

Region A (locked)

Review

Rating summary

| Movie | 5.0 | |

| Video | 3.5 | |

| Audio | 3.0 | |

| Extras | 3.0 | |

| Overall | 4.0 |

Baseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie Review

Take me out to the ball game.*

Reviewed by Martin Liebman October 5, 2010Baseball is the beautiful game that's remained virtually unchanged over the course of its lifespan, save for the faces of the Major Leaguers who take the field every day, of every summer, for what is now 30 teams, in cities all around the United States, from Seattle to Miami, from Boston to San Diego, and from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., not to mention the Canadian city of Toronto. On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers at first base, the first player to break the color barrier and open the door for future players of color, including Hall-of-Famers Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Bob Gibson; former superstars like Dwight Gooden, Barry Bonds, and Ken Griffey, Jr.; and current players such as Andrew McCutchen, Prince Fielder, and Ryan Howard. The game has evolved to embrace other ethnicities, too; Latino players are dominating the sport, many idolizing former Pittsburgh Pirates legend Roberto Clemente, while Seattle Mariners superstar Ichiro Suzuki has paved the road towards an influx of Asian-born players in the game. What was once exclusively America's pastime is now a worldwide sensation, with players from all over the world and of every color and every background competing to prove that they belong amongst the world's greatest athletes and on the same field of play as Albert Pujols, Josh Hamilton, Carlos Gonzalez, and David Price. But for all the new ways of enjoying and analyzing the game; for all the controversies and triumphs; for all the varied faces; and for the generations that have come, are now, and will in the future represent the sport; the game's immutable character and unwavering spirit will always be.

Juiced.

Much has happened since Ken Burns' 1994 documentary Baseball dazzled fans of the National Pastime and casual observers alike with its comprehensive, thoughtful, and passionate look at the history of baseball, its ups and down, its greatest triumphs and most shameful tragedies, its best players, its classic moments, and the love of the sport that's brought families together, engendered unbreakable bonds of friendship, and given hope to fans both in times of great national tragedy and once every spring when it seems that, indeed, this might very well be the year that the Chicago Cubs finally win the World Series, the Texas Rangers reach one, or the Pittsburgh Pirates regain their stature as one of the game's preeminent franchises. Since 1992, the Atlanta Braves have soared to the top of the National League standings while their NLCS opponent, the Pittsburgh Pirates, have sunk to historic lows. Four new teams -- the Colorado Rockies, the Florida Marlins, the Arizona Diamondbacks, and the Tampa Bay Rays -- have joined the league, each having appeared in at least one World Series with Diamondbacks having won once and the Marlins twice. Structurally throwback ballparks with all the modern amenities have replaced the concrete bowls of the 1970s and 1980s. The sport's most historic franchise would find a leader in Manager Joe Torre that would once again propel them to the top of the sport and rekindle a longstanding rivalry with the cursed Boston Red Sox. Owners and players would fail to agree to terms on a new collective bargaining agreement that would bring the 1994 season to a tragic halt; when baseball resumed in 1995 it needed a healer -- an Iron Man -- to bring it back to preeminence. Batted balls would leave the confines of the field in record numbers, though little did fans know that there was more than talent and hard work going on behind the scenes inside Major League locker rooms that would bring into question the integrity of the game's greatest players, its most sacred records, and the sport itself.

Top of the Tenth

He will put up numbers no one can believe.

In October of 1992, a nobody reserve named Francisco Cabrera propelled the Atlanta Braves to the World Series on a base hit to left. It was fielded by Pittsburgh's skinny superstar, Barry Bonds, who couldn't muster a good enough throw to get the gimpy first baseman and former Pirate Sid Bream out at home plate. That would be Bonds' last game in the Black and Gold; he was tired of playing second fiddle to the Bucs' center fielder, Andy Van Slyke, whom Bonds perceived as Pittsburgh's favorite, even if Bonds possessed far more raw talent than the teammate he once dubbed "The Great White Hope." Bonds -- whose father played in the majors and whose godfather, Willie Mays, is remembered as one of the game's all-time greats -- seemed destined almost from birth for the Hall of Fame. He packed his bags and, after that fateful night at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, would never play for the Pirates again, instead signing a career-defining and, ultimately, sport- and era-shaping contract with the San Francisco Giants, a team that had just barely avoided relocation to Miami and was in search of a superstar to bring the team its first-ever World Series title in the City by the Bay. The 28-year-old Bonds was already one of the game's best, and his statistics and stature only grew as a member of the Giants, though just how much growing he was really to do was yet to be seen. Meanwhile, up the Pacific coast in Seattle, Ken Griffey, Jr. -- another son of a former Big Leaguer -- dazzled with his boyish, happy-go-lucky attitude and incredible skill both at the bat and in centerfield. Armed with the sweetest left-handed swing the game had ever seen, "The Kid" seemed destined for greatness and set to turn a once-invisible franchise into a force to be reckoned with.

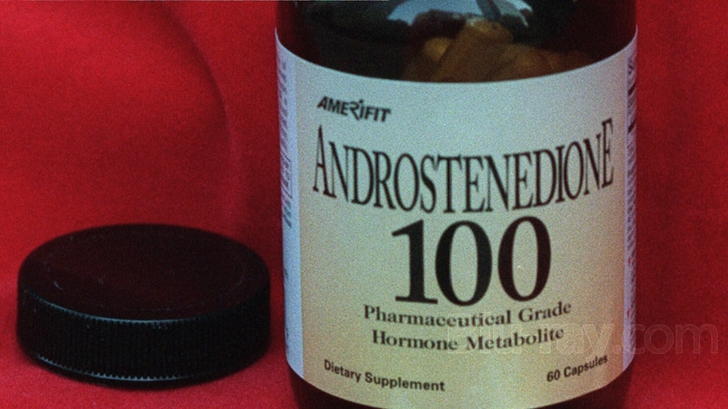

For as healthy as the sport appeared, the beginnings of a tumultuous decade-and-a-half were already taking shape. Cheating had never been truly frowned upon in the game; sign stealing by eagle-eyed and intelligent players was a regular and accepted occurrence, and pitchers who routinely doctored the baseball -- such as Whitey Ford and Gaylord Perry -- were welcomed with open arms into Baseball's Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. When in the late 1980s and through the decade of the 1990s players such as Jose Canseco -- the first ever player to hit 40 home runs and steal 40 bases in the same season -- and teammate Mark McGwire put up gargantuan numbers with the Oakland Athletics, nobody blinked an eye. Free agency, inflated contracts, high ticket and concession prices, merchandising, more fans than ever before, and greater exposure on 24-hour sports networks meant greater opportunity for the players to make big money, but to earn those extra dollars they needed to prove that they were among the elite. Suddenly, raw talent, proper nutrition, exercise, mental preparation, and hours on the practice field and in the batting cage weren't enough. The players sought an edge, something that could allow them to work harder, recover faster, and hit the ball further. They found their solution through the miracle of science, and the so-called "Steroid Era" was born. That the players may have been up to no good fell on deaf ears for years; the sport was thriving, attendance was up, and SportsCenter seemed to exist only to fill up its every hour with replays of the latest 500-foot blast or 101 miles-per-hour pitch. It wouldn't take long, however, before the situation spiraled out of control.

Nevertheless, steroids can, in some strangely roundabout way, be seen as the sport's savior. A work stoppage canceled the 1994 season, a summer that was shaping up to be one of baseball's most memorable. The Montreal Expos were comfortably ahead of the perennially favorite Atlanta Braves in the National League standings. A San Francisco Giant -- no, not that one -- named Matt Williams was threatening to break Roger Marris' single-season home run record. San Diego Padre Tony Gwynn was flirting with a .400 batting average as late as August. The strike -- a result of the player's union and owners failing to agree on a new collective bargaining agreement -- left fans jaded, and for good reason. This "millionaires versus billionaires" fiasco had robbed fans of not only a great season, but potentially alienated them away from the sport for good. Players who in a week earned as much as the average American did in a year were squabbling about contracts and salary caps, while eager young replacement players took the field but failed to draw fans. The 1995 season began late and was pared down to only 144 games, but it was one game late that summer that would turn the tide and help in bringing fans back to the ballpark and rekindle their enthusiasm for the sport. During an otherwise routine September game between the middle-of-the-pack Baltimore Orioles and California Angels, Baltimore shortstop Cal Ripken, Jr. played in his 2,131st consecutive Major League baseball game, surpassing the decades-old record held by former New York Yankee great Lou Gehrig. It was a moment frozen in time but one more than a decade in the making. One man, one ballpark, and one record was all it took for the country to once again pay attention and realize that, just maybe, that thing called The Love of the Game just might still be stirring somewhere in the soul. Still, it wasn't until several years later when two gargantuan power hitters -- later discovered to be steroid users -- would emphatically bring baseball back to the forefront of America's consciousness for good and leave the devastating work stoppage as but a footnote in the sport's vast history book.

By the mid 1990s, what had once been a stellar achievement of hitting -- the 50 home run season -- was becoming commonplace. Oakland slugger Mark McGwire had been traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, and it seemed only a matter of time before he -- or Seattle's Ken Griffey, Jr. -- would smash Roger Marris' record of 61 long bombs in a single season. Whether it was smaller ballparks, a diluted talent pool, or something else, balls were flying over Major League fences at breakneck pace. In 1998, both McGwire and Griffey were on pace to break Roger Marris' record. Then, out of nowhere, a third horse entered that race: the Cubs' Sammy Sosa, a larger-than-life figure with a smile as big as his bicep and the cheerful personality that epitomized Latin players' love for the sport that the game so desperately needed to market. He belted 20 home runs in June alone, and from then on the 1998 season grabbed the country's attention and never let go, all the way through to the season's final day. Griffey would fall off the pace but still hit more than 50 homers, but both McGwire and Sosa eclipsed Marris, with the Cardinals' Herculean slugger amassing an awe-inspiring total of 70 dingers, a number that certainly could never be topped again. For all the hype and hoopla surrounding McGwire and Sosa -- enough to even take attention away from a disastrous White House scandal -- there was one gigantic figure who wasn't pleased that the spotlight had been taken away from him. Barry Bonds, despite having achieved in 1998 the incredible accomplishment of amassing 400 career home runs and 400 career steals -- statistics that were certainly enough to guarantee him enshrinement into the Hall of Fame -- resolved to do whatever it would take to regain the national attention in the decade to come. He vowed to achieve heights even the greatest players of all time -- Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, Sammy Sosa, and Mark McGwire and Hank Aaron in particular -- could have only imagined. Meanwhile, the Atlanta Braves were still contending for the World Series year-in-and-year-out, but the spotlight had shifted to the New York Yankees, a franchise built around homegrown talent and a few key free agents. By the turn of the millenium, the Yankees were not only perennial favorites, but perennial winners; George Steinbrenner's team won the Series in 1996, 1998, 1999, and 2000. Little did the Yankees, the City of New York, baseball, and the world realize just how important a role they would play come the 2001 season, a season that would have even Boston fans rooting for their most hated rival during a period of tremendous devastation in American history.

Bottom of the Tenth

The only way to succeed is to suffer and persevere.

September 11, 2001. It was the day the world stopped turning, the day the United States suffered the largest attack on her soil since Pearl Harbor. It was no time for fun and games, and MLB Commissioner Bud Selig put a halt to play for nearly a week, allowing both players and fans alike the chance to mourn, to come to terms with what had happened, and to figure out what history had in store for not just the sport, but for the entire world. That the New York Yankees were on track to win yet another title seemed an afterthought; part of their city lay in ruin, and penant chases and playoff games suddenly seemed inconsequential in light of what transpired. Nevertheless, baseball rescued America from the clutches of agony by returning to action six days after the attacks. The New York Yankees were in the Windy City to play the White Sox, and while the devastation lay hundreds of miles away, everyone in that ballpark and across the country found that, for a time, they bled Yankee red, white, and blue. The 2001 season stretched into November, a first for the sport, and pitted the destiny Yankees against the upstart Arizona Diamondbacks, a team only granted entrance into the league a mere five years prior and already in the Fall Classic behind the power arms of two future Hall of Famers, the intimidating Randy Johnson and the overpowering Curt Schilling. The home team won every game, and the Diamondbacks enjoyed home-field advantage, spoiling the chance for a New York team to win the Series in a year it seemed only fitting they should. Nevertheless, it was an instant classic, a World Series for the ages, and despite all the problems through which baseball had suffered over the years -- a work stoppage, the terror attack on 9/11 -- the sport was back and with a vengeance. The players were stronger than ever, the Yankees were on the top of the world with arch rivals the Boston Red Sox nipping at their heels, the year prior had seen an all-New York "Subway Series" Fall Classic, and long-held and cherished records were being broken at a record pace. Baseball seemed the ultimate come-from-behind story, but the worst wasn't over for a sport that potential disaster seemed to follow with every new season.

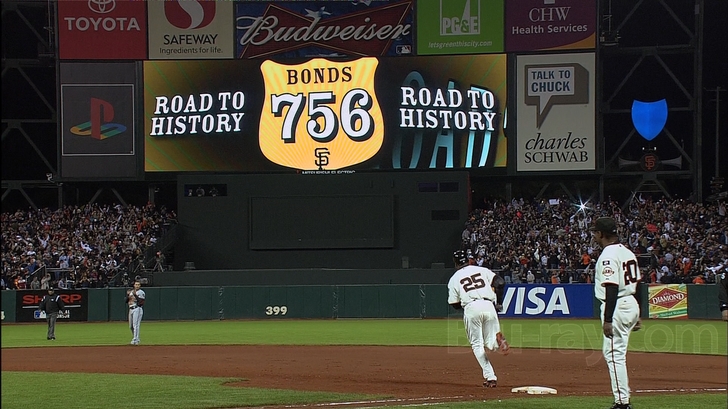

Slugger Barry Bonds -- still bitter over the way the sport dismissed his accomplishments in favor of the McGwire/Sosa drama of 1998 -- entered the 1999 season 20 pounds heavier and suddenly built like a linebacker, far from the man who came up with the Pirates as a skinny center fielder in 1986. As fate would have it, his 2001 campaign would be one for the record books, but as seemed the norm for Bonds' career, his accomplishments played second fiddle to the national tragedy and the dynasty-driven run of the New York Yankees towards a World Series appearance in the aftermath of 9/11. Nevertheless, Bonds destroyed baseballs at a record pace -- at least when a bold pitcher dared give him something to hit anywhere in the same zip code as his strike zone. Bonds blasted 73 homers that season, topping McGwire's mark by three and Marris' by a dozen. Bonds also walked 177 times that season -- a whopping 55 fewer than he would draw during the 2004 campaign -- thanks not only to a good eye, but to fearful managers who would rather put him on and watch him trot to first on four high and wide rather than jog around the bases after one deep and gone. Bonds' numbers were nothing short of staggering; nearly half of his 156 hits went out of the park, and 69% of his hits went for extra bases. He put up a .328 battering average -- excellent but not historic -- but he did pile up an unthinkable 1.379 OPS. OPS? One-base-percentage+slugging percentage. Needless to say, a great player amasses a .900+ OPS, making Bonds not only a freakishly imposing figure at the plate but the perfect example of the extremes of what sort of information baseball's revolutionary statistical analysis could accomplish. Suddenly, players were no longer judged solely on batting average, home runs, doubles, RBIs, and runs scored, and pitchers no longer by simply ERA and their won-lost record. Through his embracing and understanding of this new approach to player analysis, Oakland Athletics General Manager Billy Beane built a club that would appear in four straight postseasons to begin the decade, and his newfound ability to judge players on far more precise data and telling statistics -- and win with undervalued players -- made him the subject of the hugely successful book Moneyball by Michael Lewis. Doubters looked past the A's success on the field and claimed that the newfangled stats could neither predict nor in any way include things like heart, determination, and clutch performance into the equations, all intangibles an up-and-coming Boston Red Sox team would embrace on their march towards history.

In 2003 -- the season following Bonds' one and only trip to the World Series, a loss to in-state rivals Anaheim -- the Boston Red Sox-New York Yankees rivalry would once again capture the attention of the baseball world. The Sox entered postseason play as a 95-game-winning Wild Card team; the Yanks won the A.L. East and, with 105 wins, amassed the most victories in the league. By rule, the two teams could not meet until the American League Championship Series, should both advance that far. The Baseball gods wouldn't have it any other way, and the clubs squared off for a classic match-up. The back-and-forth series -- packed with star players and earning networks ratings rarely achieved by the sport -- came down to a seventh game that would enter into extra innings before Aaron Boone ended Boston's season with a backbreaking and potentially franchise-deflating home run; once again the boys from Beantown had been vanquished by the Evil Empire. Could they regain their footing and come back stronger than ever a year later? Meanwhile, over in the National League, the lovable losers hailing from Chicago's North Side were mere outs away from defeating the upstart Florida Marlins and heading to their first Fall Classic since 1945, hoping to actually win one for the first time in nearly a century. Baseball's other cursed franchise -- suffering at the hooves of a billy goat rather than the bat of the Bambino -- seemed destined to reach the Series until a fateful foul ball found fan Steve Bartman down the third base line. Outfielder Moises Alou made a stab at it, but Bartman -- as would any fan -- made an effort to catch the prized souvenir, disrupting the play and, supposedly, playing the part of the billy goat on that cursed night. Florida would go on to blow the game wide open, beat the Cubs in seven, and ultimately triumph over the much more powerful New York Yankees in the World Series. It's too bad the Cubs and Red Sox didn't meet in the Series that year. Two cursed teams, neither supposed to ever win it again, facing off for Baseball's biggest prize? The game would still be going strong today, tied at who-knows-what (probably 0-0) and in about the 184,000th inning, just like something straight out of W.P. Kinsella's The Iowa Baseball Confederacy.

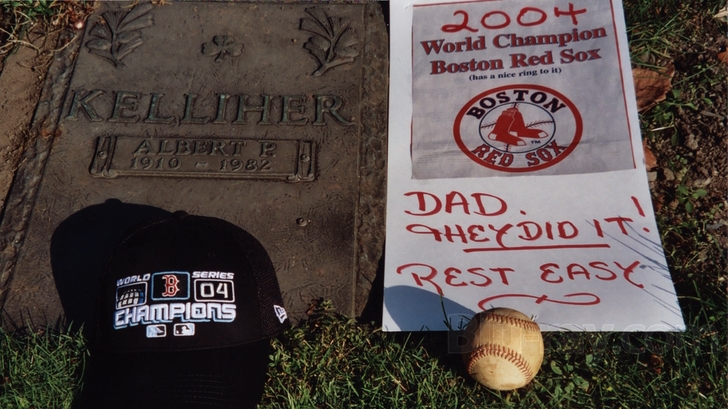

2004 would be different. Red Sox Nation -- down, battered, bruised, and left for dead -- sucked it up, wiped its nose, and seemed ready to take another crack at the hated rivals from the Bronx, ready to break the curse of the Bambino and put decades of frustration behind it. Not only had they suffered through a title drought, but they couldn't break through past the Yankees. To win the title, the Sox would have to go through Torre, Steinbrenner, Jeter, and now the team's latest hired gun, Alex Rodriguez, the converted shortstop who now manned the hot corner in the Bronx and was baseball's highest paid player and arguably her greatest overall hitter not playing left field for the San Francisco Giants. The scrappy Red Sox weren't intimidated by the Yankees' payroll and what seemed like an All-Star at every position. The Sox again finished the season in second place behind the Yanks, and once again secured the A.L. Wild Card. The Sox swept the 2002 champion Angels in three while the Yankees dispatched of the upstart Twins in four, and fate once again smiled on baseball and network executives with a rematch of the classic 2003 series. Aaron Boone was a memory -- and no longer a Yankee -- but it seemed as if 2004 would be not a repeat of 2003, but an utter disaster of epic proportions for the Red Sox. Three games into the ALCS, and Boston was in an 0-3 hole. No team in baseball history had mounted a successful comeback from such an imposing deficit, but Kevin Millar's Sox weren't about to allow history to dictate the team's destiny. An extra inning win in game four -- propelled by a late-inning stolen base by Dave Roberts -- turned into another extra inning victory in game five. The team, still down by two games, returned to the Bronx and won game six 4-2 behind the bloodied sock of ace pitcher Curt Schilling. With everything riding on the line for game seven, the Red Sox came out swinging and never looked back; Johnny Damon blasted two homers -- including a grand slam -- in an epic throttling of the Yankees to complete the comeback and propel the Sox to a World Series title over the St. Louis Cardinals, a team that never once enjoyed a lead in any of the four Series games. The wait was over. Next year was now. The curse was reversed. Thousands wept. Millions cheered. Red Sox nation was home to a World Champion.

Once again, though, baseball would travel down into a dark valley after the high of the Red Sox peak at the close of the 2004 season. In March of 2005, Jose Canseco -- writer of the tell-all book Juiced and one of the first, along with Sports Illustrated's Tom Verducci, to call to attention he rampant use of performance-enhancing drugs in the game -- appeared before the House Committee on Government Reform to testify as to what extent drugs had become part of the baseball landscape. Canseco appeared alongside Major League superstars such as Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Rafael Palmeiro, the latter three of whom vehemently denied doping. For a time, McGwire -- who refused to answer questions directly -- became the fall guy for the steroid era; Barry Bonds may have shattered his record while inching closer to Hank Aaron, but McGwire's evasion of the simplest questions painted him as a guilty party. Nevertheless, Bonds would once again become the target of public derision as word of untraceable steroids like "The Clear" and his link to Victor Conte's BALCO would further taint that superstar whose physique was now as large as his monumental blasts into McCovey Cove. This time, the eyes of the baseball world would fall squarely on San Francisco's #25, but for all the wrong reasons. His breaking of baseball's mot cherished record -- Hammerin' Hank Aaron's 755 career home runs -- was met with plenty of media attention not only for the accomplishment but for the cloud hanging over Bonds, and most fans met news of the new record with either disdain or a nonchalance unbefitting the game but befitting the athlete. Bonds had the spotlight, he had more home runs than any other Major Leaguer who ever played, and he would never again wear a Major League uniform after his record-setting 2007 campaign. The 2007 season would close with another Boston title, with the trophy changing hands to the Philadelphia Phillies in 2008 and, again, to the New York Yankees in 2009.

Baseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie, Video Quality

It's not a perfect game, but Baseball: The Tenth Inning's 1080i transfer throws together a solid enough effort made up of every piece of junk in Eddie Harris' repertoire . From classic footage to high definition splendors, from rickety old still photos to snapshots captured with the latest digital SLRs, and including newly-minted interview clips, Baseball features just about every look under the sun. The film's various standard definition material won't be judged here; far be it to reduce a score for an image's inherent quality. So long as viewers know to expect some rough-looking SD video footage -- that looks worse blown up on larger HD screens -- that makes up the bulk of the video imagery from the 1990s and the early years of the 2000s, that area of the transfer won't disappoint. Various high def segments look fine, if not slightly underwhelming. Noise and a few compression artifacts are visible around the transfer, but details and colors are otherwise impressive. The image is generally sharp, but wobbling credits and text prove somewhat distracting. Shimmering is visible on various still photographs, too. Baseball is built from a myriad of sources of varying technical proficiency; it's underwhelming stuff compared to the capabilities of today's video and photographic tools, but it's simply not fair to give this transfer a failing grade for putting on display only what it has to work with.

Baseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie, Audio Quality

Baseball: The Tenth Inning plays with a sonically unremarkable Dolby TrueHD 5.1 lossless soundtrack. This is a dialogue-intensive film, made up of interview clips and calls from the broadcast booth. Dialogue is accurate and center-focused; most is of a strongly clear and crisp nature, though a few older elements scuffle around a bit and are absent a more seamless presentation. Music is delivered across the front with evenness but doesn't quite enjoy the same level of spacing and seamlessness found on superior tracks. Rarely does the film sound downright cramped, but the minimal surround usage forces the track to play things rather close to the vest. A few Hip Hop beats and various other musical entries deliver a healthy but uninteresting low end. This track does little more than help in telling the film's story; it uses minimal effort to do so, but it delivers all it has to work with well enough. This is as routine as they come in the world of lossless audio.

Baseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie, Special Features and Extras

Baseball: The Tenth Inning goes to the bullpen for two disc's worth of extras. Disc one begins with Back to the Ballpark: An Interview with Ken Burns and Lynn Nivick (1080p, 17:12). This piece features the directors discussing the origins of their baseball documentary; the way in which Baseball is, in a way, a sequel to The Civil War and a reflection of American history and the country's narrative; the reason for making a tenth inning supplement; the original series' premiere that ran up against the 1994 strike; the journalists, players, managers, and others who provided their insights for the 10th; the challenge of capturing the essence of the steroid era; the dynamic that sees Nivick as a Yankees fan and Burns a Red Sox fan; the uniqueness of the sport; and the family connections the sport engenders. Interview Outtakes About the Era's Stars (480p, 30:33) features several of the interviewees from the film discussing Greg Maddux, Pedro Martinez, Derek Jeter, Cal Ripken, Ichiro, David Ortiz, Barry Bonds, and Joe Torre. Disc one also features several additional scenes (480p): Full of Knowledge (6:09), Dodgertown (6:05), A Tour of Fenway (13:49), A Night at Fenway (7:22), and Central Park (1:46). Disc two features only a large collection of interview outtakes (480p): Hitting and Hitters (4:47), Pitching and Pitchers (3:29), Fielding (0:33), Red Sox and Yankees (8:18), Cubs (3:42), Giants (1:10), Affirmative Action Home Runs (3:12), Late 90s Power Surge (5:41), Home Run Chase of 1998 (6:03), Asterisks and the Hall of Fame (2:44), Fame (2:58), The Flip (2:18), 9/11 (5:03), Coming to America (6:21), Globalization (0:50), Ichiro on the WBC (1:23), Rotisserie (3:20), and Why We Love the Game (3:33).

Baseball: The Tenth Inning Blu-ray Movie, Overall Score and Recommendation

Through the tumultuous two decades since the Pittsburgh

Pirates failed to advance past the NLCS for three consecutive years and thereafter stumbled towards a North American professional sports record

18-straight losing seasons, the Pirates' 1992 rival Atlanta Braves would win their division a record 14 consecutive years, the New York

Yankees would once again dominate the sport on the field and in the headlines, the Boston Red Sox would finally break the Curse of the

Bambino, an otherwise anonymous Cubs fan would cost his team a shot at immortality, the world would shrink and foreign players would make big

impacts

in the game, allegations and evidence of performance-enhancing drugs would put a damper on new records, a work stoppage would threaten to

destroy the sport, and an Iron Man would return the game to prominence. Baseball -- despite all its ups and all its downs -- has remained a rock, a

cornerstone of American life and leisure, of business and big bucks, of love and loathing, of fans and family. Who knows what the next year, the

next decade, the next century has in store for America's Pastime. All that's certain is baseball -- the perfect and persevering game -- is here to stay.

"The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled

by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game:

it's a part of our past, Ray. It reminds of us of all that once was good and it could be again. Oh... people will come Ray. People will most definitely come."

Highly recommended.

Similar titles

Similar titles you might also like

Baseball

1994-2010

When It Was a Game: The Complete Collection

1991-2000

ESPN 30 for 30: Collector's Set

Films 01-30

2009

Riding Giants

2004

Michael Jordan to the Max

IMAX

2000

First

First: The Official Film of the London 2012 Olympic Games

2012

Bud Greenspan Presents Vancouver 2010: Stories of Olympic Glory

2010

Bud Greenspan's Torino 2006: Stories of Olympic Glory

2007

Bud Greenspan's Athens 2004: Stories of Olympic Glory

2005

Salt Lake City 2002: Bud Greenspan's Stories of Olympic Glory

2003

Sydney 2000: Stories of Olympic Glory

2001

Nagano '98 Olympics: Stories of Honor and Glory

1998

Atlanta's Olympic Glory

1997

Lillehammer '94: 16 Days of Glory

1994

Marathon

1993

One Light, One World

1992

Beyond All Barriers

1989

Hand in Hand

1989

Seoul 1988

Seoul 1988: Games of the XXIV Olympiad

1989

Calgary '88: 16 Days of Glory

1989